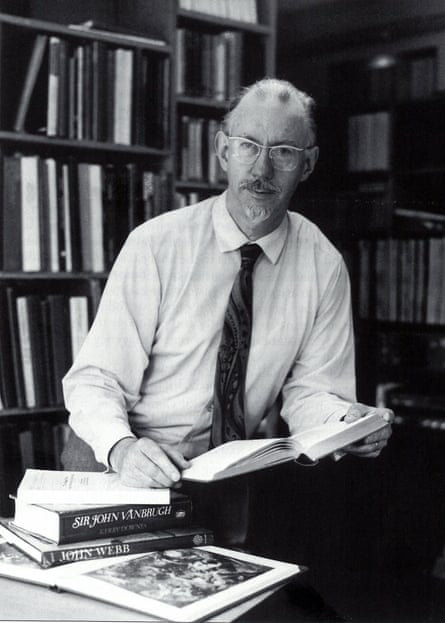

The architectural historian Kerry Downes, who has died aged 88, published two books on each of the greatest British successors of the Italian Baroque architect Francesco Borromini – Christopher Wren, Nicholas Hawksmoor and John Vanbrugh.

When he produced Hawksmoor (1959), this idiosyncratic architect was not a widely or highly regarded figure. His Christ Church, Spitalfields, was no longer in use, but the book’s appearance helped save it from destruction. Instead, a thorough restoration programme was initiated, a music festival flourished and parish worship returned in 1987.

Kerry remained a loyal defender of both church and churchyard. In pointing to the inner geometry and uncompromising juxtaposition of strikingly abstract elements in this and Hawksmoor’s other masterpieces he made the architect the focus of new imaginative attention, ultimately inspiring even the satanic psychogeographies of Iain Sinclair’s poem Lud Heat (1975) and Peter Ackroyd’s novel Hawksmoor (1985).

English Baroque Architecture (1966) was similarly groundbreaking. Even in Wren’s lifetime what came to be called Baroque was criticised by neo-Palladians as “capricious”, “chimerical” and “retaining much of what artists call the Gothic kind”. Having already outlined the extent to which Wren acted as Hawksmoor’s teacher, Kerry now saw to it that the cult that grew around the pupil would not diminish the credit due to the creator of the world’s first new Protestant cathedral, St Paul’s.

If the precise ways in which Wren and Hawksmoor were indebted to Borromini were never completely clarified by Kerry – who in any case tended to resist conventionally causal accounts of direct influence – he highlighted their common origins in Greek and Roman architecture.

In his second, more succinct, book on Hawksmoor (1969) he confirmed that the pupil diverged from Wren in according a more positive role for the imagination, or “Fancy”. He also claimed this was probably due to Thomas Hobbes’s discussion of “the effect of works of art on the emotions without the intermediacy of intellect”. Illustrative of this was the neo-Gothic brilliance of All Souls College, Oxford, of whose hall he observed: “No other roof in England shows such free plasticity, which is closer to certain rooms by Borromini or the church vaults of Central European Baroque”.

Vanbrugh (1977) demonstrated how the architect, largely self-taught, as Inigo Jones and Wren had been, benefited from Hawksmoor’s accumulated professional expertise. Their partnership was perhaps even more creative and competitive than Hawksmoor’s with Wren. They built Castle Howard, near York (the setting of Brideshead Revisited for both TV and film), surrounded by pyramids, obelisks, a classical temple and the extraordinary mausoleum for Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle; and Britain’s most magnificent Baroque sculpture-cum-country house, Blenheim Palace, near Oxford, the nation’s gift to the victorious 1st Duke of Marlborough.

After succeeding Wren as surveyor of the Royal Naval hospital at Greenwich, Vanbrugh ended up building himself Vanbrugh Castle, a Gothic fortress overlooking it. Hawksmoor meanwhile, inherited Wren’s surveyorship of Westminster Abbey and built those landmark towers that many assume to be medieval.

Sir John Vanbrugh: A Biography (1987) included Vanbrugh’s career as a playwright, before, in the words of Swift: “Van’s genius, without thought or lecture ... hugely turned to architecture.” Kerry noted the visit to Italy in the 1650s by Vanbrugh’s father, reminding the reader that none of his architects went. He did, however, discuss Vanbrugh’s sketch of a cemetery featuring domed mausoleums built by the East India Company in Surat, Gujarat, taking it that the image must have come from family contacts with eastern trade. He was characteristically generous in acknowledging Robert Williams’ later discovery that as a young man Vanbrugh had worked in India for a year and a half.

The Architecture of Wren (1982) was followed by several more studies of this astronomer and mathematician turned designer. Though Kerry was by now the world expert on the building of St Paul’s, the current consensus is that he actually underestimated his hero Hawksmoor’s role in the later stages of the cathedral’s brilliantly improvised design.

In retirement, after leaving Reading University in 1991, Kerry returned to the source of his scholarly work with Borromini’s Book: A “Full Relation of the Building” of the Roman Oratory (2009), about the Oratorio dei Filippini, of the followers of Saint Philip Neri, next to the “new church” of Santa Maria in Vallicella in Rome.

This 536-page volume featured Kerry’s complete translation of and commentary, complete with side notes and photographs, on that written by Virgilio Spada, a priest at the oratory, and Borromini himself. He was prone to anxiety and melancholy, exacerbated by intense rivalry with the smoother Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and perhaps indications of bipolar disorder. In 1667 he took his own life.

At the Oratory (despite inheriting a project which had been begun by another architect) and at his other Roman masterpieces, San Carlino, Sant’Ivo and Sant’Agnese, Borromini deployed complex geometry with extraordinary imagination. The Oratory’s curved brick facade misleads as to what is behind in a way reminiscent of Hawksmoor’s Codrington Library at All Souls where a Gothic exterior conceal a classical interior.

Kerry was the son of the organist Ralph Downes and his wife Agnes (nee Rix), and was born in Princeton, New Jersey, where his father was musical director at the university’s new chapel. The family returned from the US and in 1936 Ralph, a Catholic convert, took up his post as organist at the Brompton Oratory, London, where he remained until 1977; from 1948 he designed and oversaw the organ at the Royal Festival Hall. A Bach specialist, he was a pioneering promoter of the musical Baroque, much as in the field of architecture was Kerry, who seemed to have inherited some of his father’s professional doggedness as well as his faith.

At St Benedict’s school, Ealing, Kerry’s art teacher, Michael Franks, encouraged his interest in the Baroque, with the result that he would cycle into central London to visit the churches, armed with a wooden quarter-plate camera. The art history degree at the Courtauld Institute suited what he called his butterfly mind: “I was painting, learning photography, and developing what is still a major interest: why the world in general, and buildings in particular, don’t look as they do in pictures and photographs.”

His first architecture essay there was for the director, Anthony Blunt, already from 1945 surveyor of the King’s pictures, who subsequently observed: “Once Borromini has bitten you he never lets go.” Blunt’s own book on the Italian architect followed in 1979, the year that he was exposed as having been a Soviet spy.

After gaining a BA in 1951, Kerry embarked on his PhD on Hawksmoor with Margaret Whinney; it was awarded in 1960, the year after the publication of his book. During the project’s gestation he was a librarian at the Courtauld (1954-58) and then at the Barber Institute, Birmingham University. In 1966 he took up the post of lecturer at Reading, where I and many others benefited from his wide-ranging expertise. After his appointment as professor in 1978 he continued to invite Blunt to lecture, his disgrace notwithstanding.

As well as campaigning for Hawksmoor, Kerry took an expert interest in modernist architecture, and supported the Mansion House Square office block in the City of London that Mies van der Rohe designed in the 1960s. Richard Rogers described it as “the culmination of a master architect’s life work” and Prince Charles as “a giant glass stump”: in the event, James Stirling’s No 1 Poultry was built on the site. A sympathetic teacher of Baroque painting and sculpture as well as architecture, Kerry also wrote a book on Rubens (1980).

He was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1961, and served as a member of the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (1981-93) and as president of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain (1984-88). In 1994 he was appointed OBE.

At the Barber Institute he met Margaret Walton, a music librarian with a contralto voice. They married in 1962 and remained a devoted couple until her death in 2003.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion