To Imagine a Better Future, Look to John Rawls

While we cannot change the world with dreams alone, moral ideas can inspire people to come together and change their societies for the better.

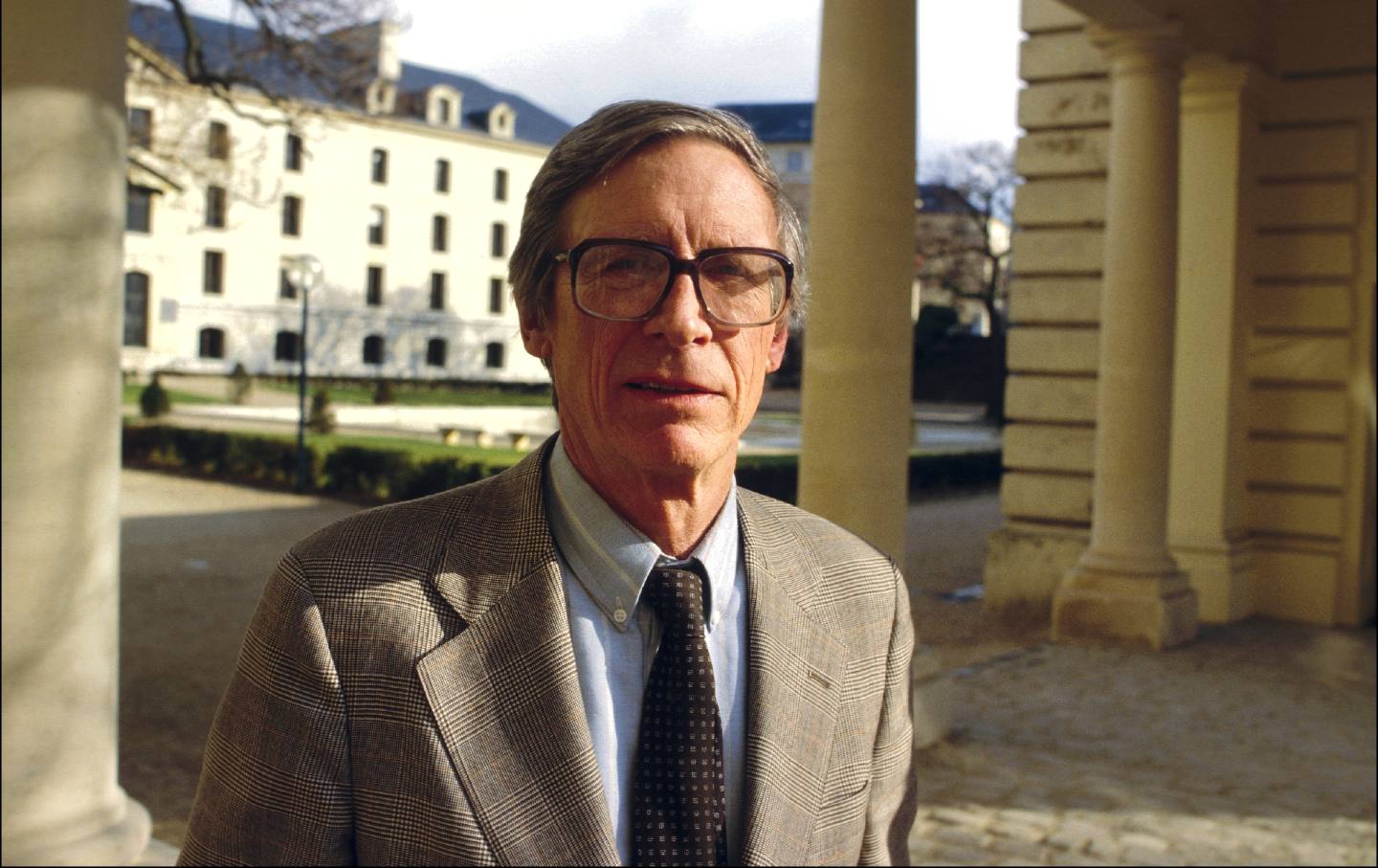

John Rawls in 1987.

(Frederic Reglain / Gammo-Rapho via Getty Images)What would a fair society look like?

Most of us—and by “us” I mean citizens of the world’s rich democracies—would agree that the societies we live in are far from fair. And yet, while our societies face many common challenges—cultural polarization, loss of trust in politics, inequality, ecological crisis—on nearly every dimension these problems are at their most extreme in America. Indeed, the recent history of the United States is a cautionary tale of the dangers of unbridled capitalism and its capacity to corrupt democracy, stunt opportunity, and sow social discord.

Much has been written about the nature and causes of these problems, and we now have an increasingly sophisticated diagnosis of our current ills. What is much harder to find is a coherent vision of what a better, fairer society would look like. Since the 1980s and the rise of neoliberalism, our political discourse has become increasingly narrow and technocratic. We have, in the words of the philosopher Roberto Unger, been living under a “dictatorship of no alternatives.” This is not a problem only for those of us who think our societies stand in need of far-reaching reform. It is this moral and ideological vacuum at the heart of our politics that has made space for the rise of illiberal, antidemocratic populism.

Of course, debate hasn’t stopped entirely. The sense of crisis across the world’s liberal democracies has created space for fresh thinking, and there is growing interest in some pretty radical ideas, from citizens’ assemblies to a universal basic income. What we lack is an underlying ethical or ideological framework that can bring disparate policy proposals into a coherent whole. We need a new philosophy—a vision of the common good that builds on, rather than rejects, the core values of liberal democracy and that can inspire people to transform their societies for the better. After all, without a clear idea of where we want to get to, how can we know that we are on the right course? At stake is more than just the next election—it is the chance to shape a new political consensus for the post-neoliberal age.

And yet, while politicians like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher—the architects of neoliberalism—could look to thinkers like Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, to whom can progressives look for fresh inspiration today?

There is growing interest in Karl Marx and the democratic socialist tradition, which undoubtedly has much to offer. But Marx was famously reluctant to spell out a vision of what a just society might look like, and contemporary socialist thinking is often stronger on what’s wrong with capitalism than what would replace it.

The most powerful resources for developing such a vision today lie in the liberal tradition, and specifically the ideas of arguably America’s greatest-ever political philosopher: John Rawls.

Rawls’s magnum opus, A Theory of Justice, published in 1971, revolutionized political philosophy and earned him a place in the canon of great Western thinkers. According to the prominent socialist philosopher G.A. Cohen, there are “at most two books in the history of Western political philosophy [that] have a claim to be regarded as greater than A Theory of Justice: Plato’s Republic and Hobbes’s Leviathan.” Rawls’s great achievement was to fuse the classical liberal commitment to freedom with a concern for equality more often associated with socialism, creating a synthesis that has come to be known as “liberal egalitarianism.” What makes his ideas so vital right now is that they are fundamentally hopeful and constructive, providing us with what he called a “realistic utopia”—an achievable vision of the best that a democratic society can be. They are an essential antidote to widespread cynicism and an unparalleled resource for developing a unifying and transformative progressive politics.

Rawls’s philosophy is also surprisingly easy to grasp. At its heart is a strikingly simple idea: that society should be fair. To work out what that means, we should imagine how we would organize society if we didn’t know our position within it—whether we would be Black or white, gay or straight, rich or poor—as if behind a “veil of ignorance.”

If we imagined society in this way, he argued, we would choose two principles of justice. First, we would want to protect our most important personal and political liberties, including freedom of speech, association, and bodily autonomy, as well as equal voting rights and opportunities to influence the political process more broadly. After all, if we didn’t know who we would end up being in society, we wouldn’t want to risk being persecuted for our religious beliefs or sexual preferences or being denied the right to vote because of our gender or the color of our skin.

This “basic liberties principle” is what makes Rawls’s theory distinctively liberal. His second principle, which has two interlocking parts, gives his theory its egalitarian flavor. All of us, he argued, would want “fair equality of opportunity”—not just the absence of discrimination but a truly equal chance to develop and employ our talents irrespective of class, race, or gender. At the same time, we would permit inequalities only where they ultimately benefit everyone—say, by encouraging innovation and growth—and we would organize our economy to maximize the life chances of the least well-off: the so-called “difference principle.” If those who have the least can accept that society is fair, then surely those who have more can do so too.

Alongside these two principles we would recognize our obligations toward future generations by adopting the “just savings principle,” according to which we have a duty to maintain the material wealth and vital ecosystems on which society depends—a duty we are spectacularly failing to live up to today.

While Rawls was writing in the 1970s, his ideas are especially relevant now. At a time when individual freedom and democracy are under attack, they offer a much-needed affirmation of a free, tolerant, and democratic society, where people with different beliefs about religion and morality live together in a spirit of mutual respect and where we agree to resolve our differences peacefully through the ballot box. His basic liberties principle provides a moral compass for navigating fraught “culture war” debates from free speech to abortion, gay rights, and religious freedom, and for building a truly inclusive sense of patriotic identity. At the same time, it points toward practical changes that would both protect and reinvigorate democracy—depoliticizing judicial appointments, capping private donations while introducing a countrywide democracy-voucher scheme, proportional representation, and expanding the role of citizens’ assemblies.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Crucially, they show us how we can combine freedom and democracy with true economic justice. Indeed, it is when it comes economic question that we really see the profound implications of Rawls’s ideas.

This must start with urgent action to avert ecological and climate breakdown through massive public investment and an economy-wide carbon “tax and dividend” scheme, leaving all but the richest 30 percent better off. And sustainability must go hand in hand with achieving real equality of opportunity and shared prosperity. This would require universal early-years education, funding schools based on need rather than local wealth, direct subsidies for higher education combined with publicly funded income-contingent loans, and a broad program to tackle entrenched racial and gender inequalities.

Beyond this, we must build an economy that is not only more equal but more humane, where even the lowest-paid workers are treated with dignity and respect, and where each of us has a real opportunity to find work that can be a source of creativity, community, and personal fulfillment. A universal basic income would provide a vital foundation of security and independence for all. But we cannot simply compensate for market inequalities through taxes and transfers. Rather, we must change the underlying structure of our economy itself: strengthening unions and increasing the minimum wage, giving everyone a fair share of society’s wealth through a citizens’ wealth fund, and putting workers on the boards of most if not all companies.

In recent years, “liberal” has become a term of abuse on both left and right, and criticizing it has become a catch-all for expressing discontent with the state of society today, from soaring inequality to family breakdown and a wider sense of social and spiritual alienation.

These critics are not entirely wrong in pointing the finger at something called “liberalism”: Neoliberalism, which is characterized by an almost religious faith in the market, has dominated political discourse in recent decades, and it is responsible for many of the problems we face today. But liberalism is not a single set of ideas or policies but a broad and evolving intellectual and political tradition. One of the ironies of this period is that just as neoliberalism was coming to dominate politics, liberal philosophy—thanks largely to Rawls—was moving in almost the opposite direction. The cornerstones of modern liberal philosophy are cooperation and reciprocity—not selfish individualism. And whereas classical liberals and neoliberals from Adam Smith to Friedrich Hayek have defended laissez-faire capitalism, Rawls stands in a long tradition of “social liberal” thinkers like John Stuart Mill, John Dewey, and John Maynard Keynes who’ve recognized the vital role of the state in shaping and harnessing the benefits of markets for the good of all.

Reinventing liberalism as an intellectual tradition is not an end in itself. It is the starting point for developing the kind of galvanizing and broad-based vision that has been missing from progressive politics. Rawls’s ideas embody the deep respect for different ways of living that is the key to transcending the culture wars; they represent a unifying alternative to divisive forms of “identity politics,” connecting the injustices faced by people of color, women, and the LGBTQ+ community to the struggle for universal values of freedom and equality; and they point us toward an economic agenda that would address the long-neglected concerns of lower-income voters, for not simply higher incomes but also a sense of independence, meaning, and social recognition.

What are the chances that these lofty ideals will have a meaningful impact on real politics? How can we overcome the inevitable resistance from entrenched elites whose hold on political power and economic resources would be challenged by them? These are difficult questions for any progressive agenda. But what is politically achievable is not predetermined—it depends on what people believe in and are willing to fight for. Many of the things we take for granted today—freedom from slavery, universal suffrage, the existence of the welfare state—were once mere figments of the imagination of idealistic reformers. While we cannot change the world with dreams alone, moral ideas about justice, freedom, and equality, backed up by practical ideas about how we can change our institutions, can inspire people to come together and change their societies for the better.

At a time of social division and even crisis, it might seem naïve to turn to philosophy. But, as Rawls argued, it’s precisely in moments like this, “when our shared political understandings…break down,” that we need philosophy the most. The questions that divide American society most deeply today—about the scope and limits of individual freedom, and the economic obligations we have toward our fellow citizens and future generations—are fundamentally moral ones. The task of philosophy is, as Rawls put it, to “focus on deeply disputed questions and to see whether, despite appearances, some underlying basis of philosophical and moral agreement can be uncovered.” While we’re unlikely to agree on everything, we can at least hope to narrow our differences “so that social cooperation on a footing of mutual respect among citizens can still be maintained.”

Like other democratic societies, America has faced periods of impasse before, when it has been divided at the deepest level—the Civil War, the Great Depression, struggles over civil rights in the 1960s. The immediate resolution to these conflicts came from mass political action, not philosophy; and it is through democratic politics that we must strive to find a peaceful way out of the challenges we face today. But as in those periods, the challenge facing progressives is not simply to win votes but to change minds: to forge a new consensus about our guiding values, how to interpret them, and how to make them a reality.

I often find myself coming back to a particular quote that, I think, captures what is so unique and inspiring about Rawls’s ideas. It comes from the philosopher Thomas Nagel’s review of A Theory of Justice in 1973. “The outlook expressed by this book is not characteristic of its age,” Nagel wrote, “for it is neither pessimistic nor alienated nor angry nor sentimental nor utopian. Instead it conveys something that today may seem incredible: a hopeful affirmation of human possibilities.” We need this kind of outlook today more than ever.

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that moves the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories to readers like you.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation

Angela Alsobrooks Beat the Big Money. Now She Has to Beat the Big Republican. Angela Alsobrooks Beat the Big Money. Now She Has to Beat the Big Republican.

Maryland’s new Democratic US Senate nominee won a bitterly contested primary. Now, she has an even tougher fight on her hands.

The Media Keeps Asking the Wrong Questions About Biden and the “Uncommitted” Vote The Media Keeps Asking the Wrong Questions About Biden and the “Uncommitted” Vote

Expecting voters to support the person with the power to stop the killing of their families, but who refuses to use it, is asking the impossible. This is about now, not November.

Michael Cohen’s Testimony Reveals the Sad Life of a Trump Toady Michael Cohen’s Testimony Reveals the Sad Life of a Trump Toady

Trump’s former lawyer described in court how the former president demands total sycophancy from his underlings.

Biden’s Domestic Reforms Don’t Add Up to the Great Society Biden’s Domestic Reforms Don’t Add Up to the Great Society

But they do signal that government can make life tangibly better.

How Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Brain Became the Diet of Worms How Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Brain Became the Diet of Worms

Can a presidential candidate afford to lose gray matter to parasites?

Could an Abortion Rights Referendum in Missouri Give Democratic Candidates a Chance? Could an Abortion Rights Referendum in Missouri Give Democratic Candidates a Chance?

The party has strong candidates up and down the ballot, and a referendum could bring out enough young voters to turn this red state purple.