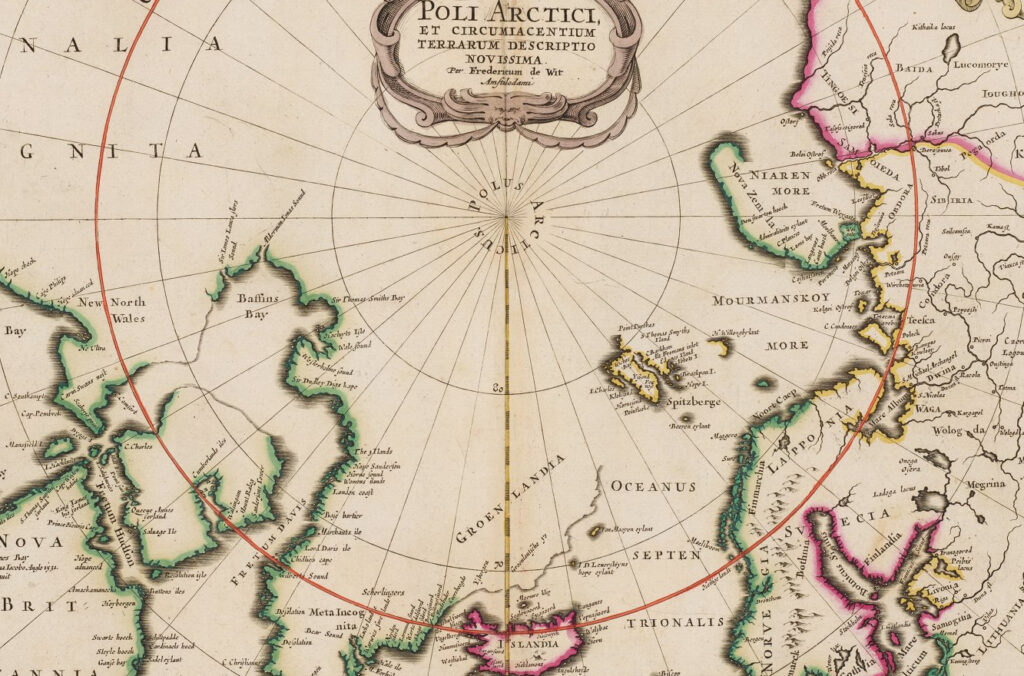

Small Ocean, Big Hype: Arctic Myths and Realities

Editor’s Note: This is the first part of a short series examining maritime geography and strategic challenges in specific bodies of water, ranging from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Guinea and the South China Sea.

The Arctic Ocean may be the world’s smallest but it looms large in the imagination. Remote and unique, the Arctic is, for some at least, the most romanticized ocean in the world. It has been fueling legends and ambitions for centuries, and continues to fuel new geopolitical myths today.

Global dynamics, from climate change to the decline of American hegemony and technological revolution, are reshaping the Arctic. Unfortunately, mythmaking about the Arctic continues to distort the narratives available to both public and elite audiences. Heather Exner-Pirot beautifully explains how easy this can be and, as Josh Tallis has written, the phantom of Arctic misgovernance can be used to raise alarm about an unusual gap in Arctic security governance. In reality, though, the Arctic is profoundly normal.

The following is an effort to disassemble the leading myths about the Arctic Ocean and to underscore nuggets of truth underlying the legends. The natural tendency, noted above, for people to process their understanding of the Arctic through the most dramatic filter possible, is not easy to counteract by listing mundane realities. But falling for the hype is not a good way to make policy. Refuting these myths can put the focus back on more mundane, but ultimately more valuable, solutions.

The Legendary Arctic Scramble

Most of the modern Arctic myths and legends are spicing up mundane realities with added drama. For example, it’s common to see the Arctic referred to as a battleground for valuable natural resources. It’s the “$1 Trillion Ocean”, holding massive reserves of oil and gas (or one trillion dollars’ worth of critical minerals, take your pick), with echoes of Dr. Evil. Competition over resources is framed as a “race” or “battle,” although it is often unclear what winning might mean. Industry and science have long known that the Arctic holds a significant endowment of natural resources. Prospecting and development in the Arctic lag behind that of other regions due to the significant logistical challenges and resulting extra costs relating to arctic operations. Resource deposits in the Arctic must be of a higher grade or size to attract investors and overcome the added risk to capital. In short, it has historically been cheaper to look elsewhere. And that largely remains true: There has not been a flood of investment and new development into the Arctic.

Rather than unclaimed, ungoverned space, the Arctic Ocean and surrounding landmass are almost entirely sovereign lands and waters of the eight Arctic states. Yes, there is a small area of high seas, the central Arctic Ocean. This area is under a fishing moratorium and can only be accessed through traversing an Arctic state’s waters (plus likely stopping in an Arctic state port). And yet the myth of an Arctic wild west persists: “As a consequence of the rapidly disappearing polar ice caps, there has been an increase in unclaimed ocean and land territory, beyond any nation’s control, that countries are attempting to claim jurisdiction over,” proclaims one analysis. While this is a common argument, it is factually incorrect. It is linking two separate issues into one misleading causal chain: the decline in Arctic sea ice due to climate change, and the ongoing process of defining boundaries and spaces under international law. In fact, there is no unclaimed land territory in the Arctic. And there is just one maritime boundary disagreement, between the United States and Canada, over a tiny slice of the Beaufort Sea.

Perhaps the “Great Arctic Race” is about the overlapping claims to the central Arctic Ocean seabed. The U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) permits coastal states to claim areas of the extended continental shelf beyond the 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone, if they can prove that these areas are a natural prolongation of their continental shelf. Russia, Denmark (via Greenland), and Canada have overlapping claims in the central Arctic. Thus far, they have all adhered to the process of defining these claims in accordance with international law. Russia’s law-abiding approach to the Arctic shelf claims is a rare bright spot in the country’s foreign policy.

The U.N. convention and seabed claims have been in the spotlight recently as interest grows in seabed mining for critical minerals. Seabed mining is not likely to drive conflict over Arctic shelf claims. The central Arctic Ocean — over 200 nautical miles from any coast — is also an incredibly inhospitable area for resource extraction. The Arctic Ocean still freezes in the winter, and is sunk in the frigid darkness of the polar night. The seabed mining industry, like most global industry, is likely to look for less costly options in warmer latitudes. While it cannot be assumed that Russia will continue pursuing its shelf claims in accordance with international law, it is likely to use lower-cost tools like lawfare or information warfare to complicate central Arctic Ocean claims, rather than apply high-cost and hard-to-sustain military options.

The Myth of Increasing Accessibility and Arctic Shipping

The idea that climate change is increasing accessibility in the Arctic is repeated so often that it is taken for granted. There is an element of truth here — the thick cap of multiyear Arctic sea ice that has shaped the region for thousands of years is melting away and will soon be gone. But that is just one piece of a bigger puzzle, and the net effect of climate change in the Arctic is making human activity harder, not easier.

Shrinking sea ice leaves coastlines unprotected from stronger, more frequent storms. Coastal erosion is higher in the Arctic than anywhere else, threatening U.S. radar installations. Thawing permafrost causes subsidence, destroying infrastructure and saddling Arctic states with massive costs — highest in Russia. Permafrost thaw will cause many more disasters in coming years, in Russia and elsewhere. Massive wildfires further endanger communities and infrastructure in the North. At sea, increased storminess and stronger waves create hazards, along with increases in drifting ice. At the heart of it all lies uncertainty — a powerful dissuading factor.

Arctic shipping lanes replacing Suez and Panama is another related myth. When crisis erupts in the Red Sea, the Suez Canal, or the Panama Canal, it is tempting to point north to emerging Arctic shipping lanes as alternatives. On paper, Arctic shipping routes appear to offer considerable savings of distance, time, and fuel between northern ports in Asia, Europe, and North America. However, in practice, these shipping routes remain largely notional. Over the last decade, destinational Arctic maritime activity has ticked up, mostly driven by Russia’s Yamal liquified natural gas project and expansion at Canada’s Mary River Mine. Container ships and roll-on roll-offs are barely present, and this type of traffic has showed no change in the past decade.

It is clear that Canada has no interest in opening the Northwest Passage to international shipping. Furthermore, the complex routes of the passage have draft limitations, significant remaining ice, and inadequate charting. While Russian President Vladimir Putin has been personally driving the effort to develop the Northern Sea Route, imposing an ambitious timeline for cargo growth, reality is not keeping pace. The route is plagued by its own draft limitations and lack of supporting infrastructure, as well as unpredictable ice hazards. International shipping vanished following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and while cargo totals have rebounded and grown in the past two years, the Northern Sea Route is functionally a route for Russian-flagged ships of all sorts to carry oil and gas to Asian markets (and bring in construction materials for future developments, which have been weakened by sanctions).

The Myth of Russian Dominance and American Indifference

A large body of mythmaking threatens to create a security crisis in the Arctic by sketching a 10-foot-tall Russia intent on conquering the region and controlling the ocean and casting the United States as an impotent weakling. These outsize legends are used to justify massive spending increases in the Arctic, as well as significantly stronger measures against Russia, both of which could contribute to escalation in the region and also ripple across the global balance.

Russia’s so-called “dominance” of the Arctic has been treated as gospel. It is true that over half of the Arctic coastline is Russian territory, and nearly half of the people living in the Arctic live in Russia. And yet the discourse of Russian dominance in the Arctic goes beyond geography. It also presents Russia’s position as a threat to the United States and to the entire Arctic Ocean. Of course, Moscow does everything it can to nourish this sense of threat. Planting a flag at the seabed of the North Pole — possibly the most effective Russian public relations stunt ever — was a purely symbolic act, but continues to serve as a reference point. Dropping paratroopers at the North Pole, or unfurling a giant banner on the ice, are also gestures that feed the legend.

Arguments about Russia’s so-called dominance of the Arctic reveal more about America’s own insecurities than the facts on the ground. This framing creates a sense of unnecessary urgency and relies on a set of measures that together would badly warp U.S. strategic planning. Part of this is the legendary icebreaker gap, thoroughly debunked by Paul Avey. Does Russia dominate the Arctic with its icebreakers? Or does it just have a reasonable number of icebreakers for its 24,000 kilometer Arctic coastline, along which Putin is desperately thirsting to build an international shipping lane that has so far failed to catch on? Sober analyses of Russia’s power and strategy in the Arctic need to be facts-based, rather than dealing in terms of dominance.

Yes, Russian military capabilities and capacities in the Arctic are substantive. It is widely recognized that Russian leadership began to rebuild and expand Arctic military capabilities and capacities as soon as it was able to, starting in the early 2000s. Most authoritative analyses note that these installations and systems are primarily defensive in nature, intended to help control and protect Russia’s economic and strategic interests in the Arctic, although they could of course be useful in supporting aggression and, as Katarzyna Zysk notes, Russian strategic thinking does not clearly differentiate between offence and defense. All great powers have military bases along their coastlines, and Russia has both strategic and economic interests to protect in its Arctic territory.

And if fears over Russia are not enough, another myth holds that China is coming for the Arctic. Or that Chinese-Russian cooperation will open the door for Chinese dominance in the Arctic. As Marc Lanteigne has explained, relations between Beijing and Moscow in the Arctic are far more complicated. And others have noted that the myth of China’s growing influence in the Arctic is mostly serving Beijing’s interests. It is important to watch the broader trajectory of Russian-Chinese relations and not rush to assumptions about China’s future in the Arctic.

In parts as a result of fears over Russian dominance, claims that the U.S. Department of Defense “needs to do more in the Arctic” have also become commonplace. The United States has identified several critical gaps in operational capabilities and capacities in the Arctic, including in the National Strategy for the Arctic Region as well as the Department of Defense’s Arctic strategy. The most significant gap is the North Warning System, and the ongoing effort to replace this critical system. Canada has also underscored its commitment to upgrade the key continental defense architecture, most recently in an Arctic-focused defense policy update. But it’s also important to note that the United States has significant Arctic military capabilities, including the highest concentration of fifth-generation aircraft in the world, as well as an airborne division in Alaska, along with a North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) region. U.S. Navy submarines operate and train regularly in the Arctic Ocean.

In the current budget context, in which the Department of Defense faces flat and tight budgets, there are not free-floating resources to build up any but the most vital capabilities in the Arctic. Broad calls for significant spending increases in the Arctic are divorced from the reality of spending needs in the Indo-Pacific and Europe, and from U.S. national strategic priorities.

The Real Monster: Climate

It’s also become commonplace to say that the Arctic will be increasingly threatened by climate change. Unfortunately, if there’s anything false about this claim, it is that the threat is already here. The Arctic is actively, rapidly undergoing climate-driven catastrophic transformation right now. On any reasonable timescale for climate mitigation, the Arctic as we know it now will be gone. An ice-free Arctic Ocean in September, the time of year when sea ice is at its minimum, may come in the next few years, and ice-free conditions are expected by as early as 2035. While sea ice can grow back if warming factors are reversed, other environmental changes in the Arctic are climate tipping points, including permafrostcarbon.

Myths help us make sense of a world we do not understand. The Arctic Ocean has been wrapped in myths precisely because it is little understood — as are both polar regions. Even Antarctica, which is as far from the Arctic as geographically possible, is dragged into Arctic mythmaking: “Absent military confrontation, the United States will not contain the ambitions of China and Russia in the remote regions of the Arctic or Antarctica.” While there are good reasons for the U.S. government to pay more attention to Antarctica and the rules-based order there, the two regions are very, very different.

It is easy and tempting to rely on the Arctic mythology outlined above. These legends and symbols are part and parcel of centuries of stories about the Arctic that reflect truths from farther south. Some of the language about the Arctic, particularly the concerns of Russian dominance, is freighted with cultural fears about the United States “wimping out.”

It is more enjoyable to build up bogey monsters in the Arctic than it is to figure out how to pay for aerospace defense modernization. It is easier to count Russian icebreakers than to solve the U.S. Coast Guard’s icebreaker woes. It is far simpler to call for a U.S. Navy fleet in the Arctic (or combatant command, or NATO command) than to solve the Navy’s shipbuilding woes, strategic woes, or ethical woes. It is also far more comfortable to focus on competition with Russia and China in the Arctic, and all the ways in which retreating ice gives us more ways of focusing on that competition, than to think about where the ice is going. It is definitely easier than stopping climate change.

And yet. The only way to understand the Arctic is to look beyond the legends, to talk to those who live there — and to place the Arctic Ocean in its global context. It is not an ocean apart. The world’s oceans flow together in a colossal watery belt, and are best understood as such. If Washington wants to tackle problems in the Arctic, it should focus on the big, hard problems: talk seriously with Canada to fund and reinvent NORAD, invest in and pursue new solutions to shipbuilding, and move faster on climate change on many different fronts.

Rebecca Pincus, Ph.D., is director of the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center. She was a contributing author on the 5th National Climate Assessment, and served as Climate and Arctic Strategy Advisor in Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy. She previously was on the faculty at the U.S. Naval War College.

Image: Rumsey Map Collection

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to Canada’s Red Dog mine instead of its Mary River mine.