This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Not long after arriving in New York, Sarah McNally, a devoted vegetarian, tried oysters for the first time with the family of a boyfriend. She loved them — 25 years later and still vegetarian, she still makes an exception for them — but she equally loved their craggy, opalescent shells, which she gathered up afterward and, to the polite horror of her hosts, stuffed into her purse.

At 49, McNally has a soft, fluty voice (with a trace of rounded Canadian oars: “Soary,” she would apologize) and a wide-eyed manner. She’s too direct to be a classic bullshitter, but the oyster story painted a portrait almost too fanciful to believe. It felt like something out of a 19th-century novel: The provincial innocent from the North making her way in the sophisticated city, the magpie magnetized by the overlooked beauty of the world.

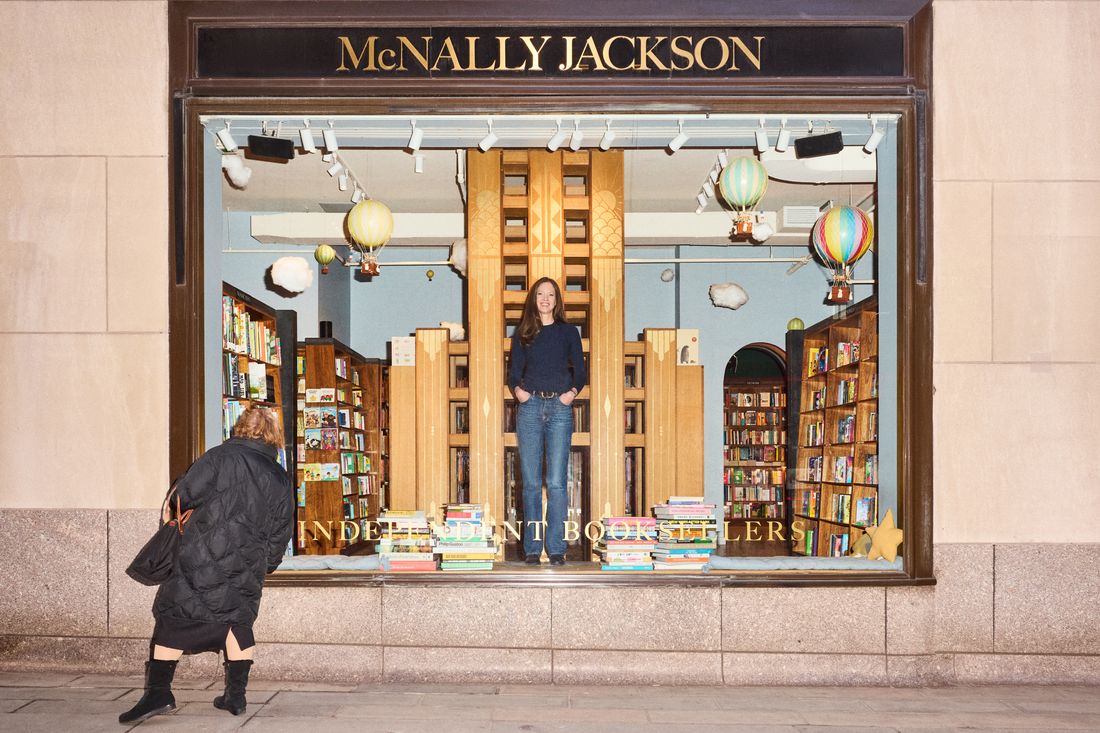

McNally considers herself a humble bookseller. She is also the founder and owner of an ever-expanding empire, McNally Jackson, now likely the third-largest buyer of books in the city, after only Barnes & Noble and the Strand. In December, the company celebrated its 20th anniversary. Over the course of the past two decades, as many independent booksellers closed their doors, what began as a single shop on Prince Street has become five. Among them, readings and launches are hosted most nights of the week, and happy are the authors who manage to secure a spot. “McNally Jackson,” one novelist said, “conveys prestige better than anyone else.”

McNally’s is a thumb on the scale of cultural life in the city. She hosts several book groups at the stores and privately runs several more. Hang around literary circles long enough and word will reach you that she is reading Middlemarch with Claire Danes and Hugh Dancy and has read Clarice Lispector with David Byrne and Esther Perel. (“If you go to Shabbat at her house,” she told me of Perel, “she’ll always pull out her guitar.”)

McNally is professionally bashful about such associations. She insists she isn’t interested in the glow of fame. “Book people, we all live in refracted glory,” she said. “We’re not people who are looking for the spotlight.” Tall and beautiful, she speaks in full, carefully reasoned paragraphs that unfurl extemporaneously. She is earnest in an era of irony, and it can be unnerving to encounter someone who says, with a straight face, that a bookseller is “someone who loves people, trusts people, believes that almost any stranger can read something extraordinarily good”; that bookselling exists at the “intersection of loving people and loving books.”

McNally generates what seems like millions of ideas in a single conversation, and over the months I spent with her, she considered a new imprint, a new shop, and a nationwide book-of-the-month program and even mused with enough seriousness about addressing homelessness that I wondered whether she intended to run for office. “A terrifying thought,” her ex-husband, Chris Jackson, said with a laugh.

McNally still sees herself as the girl scooping up the oyster shells — she’s still selling the story, after all. But that naïveté is balanced by an unstinting intensity, a drive to build or bend the world into her better image of it. Her New York is a place where we are all only one read away from our best selves, lacking only the space to dig in. She is there to provide. “I want people to know that they can trust us with their reading life, that this is not a sloppy nor commercial project,” she said with characteristic fervor. “I am working at the limits of my ability and doing so for what I believe is a good cause: the life of the mind in New York City.”

McNally was born in 1975, the daughter of an academic and a social worker. Her father, Paul, was estranged from his engineer parents for the crime of getting a Ph.D. in Romantic poetry. It was his pursuit of tenure, ultimately unfulfilled, that bounced the family from Kingston, Ontario, to comparably remote Winnipeg, Manitoba. Her mother, Holly, gave up her career as untenable as the family moved around. Eventually, she had the idea to open a bookstore, and McNally Robinson — her surname joined with that of her first business partner — opened in 1981. Sarah shrugged when I asked why: “It’s just sort of an idea she had. Which is all the same with me.” This wasn’t quite true. By the time her parents sold it to their employees in 2012, McNally Robinson had grown into one of Canada’s largest independent bookstore chains.

McNally “didn’t have the easiest childhood,” her friend Paola Prestini, the founder of the Brooklyn music venue National Sawdust, told me. Expectations were fierce. “My family didn’t believe in allowance,” McNally said. “I had my first job at 8. I had to wake up before school and deliver newspapers. You can’t imagine. It’s so cold that your eyelashes freeze shut because of the condensation from your eyeballs, which are tearing.” Then she got an after-school paper route as well. She’s spared her teenage son, Jasper, from that grind. “You’re ruining that boy,” her parents tell her. “And I’ll say, ‘You ruined me,’” she said. “I cannot stop working.”

At 13, Sarah began working in the back room at McNally Robinson. She would receive the deliveries (she remembers intercepting a book her mother had special-ordered for her, about getting your period, before any of the other employees could see it). “I fell for it right away,” she said. “I still remember every bookseller I worked with back then.”

After studying philosophy at McGill, in Montreal, McNally graduated without a clue what to do. By that time, her family had found success — money was not an issue, if it had ever been — and she spent a year and a half traveling solo through East Africa before landing in New York in 1999. “She will never go back to Canada, I think,” Prestini told me. A love of reading, she said, “that’s the one tether, the one thing she got.”

In New York, McNally looked for work in publishing. After an unsuccessful interview with the head of the publisher Little, Brown, she realized she had a problem: “To actually make your way, you need a certain amount of chutzpah,” she said. “And I had none at that time. And you also have to believe that the world would want you to some degree, and I didn’t enter the world with that belief.”

She eventually secured a junior-editor role at Basic Books but hated being trapped behind a desk. In 2004, she married Chris Jackson, a rising young editor at Crown, and shortly after that decided to open her own McNally Robinson with some money from her grandfather. (It was a few years before it was rechristened McNally Jackson — less after him, Jackson has said, than after their son, who was born in 2008.)

McNally applied particular diligence to choosing the best location, consulting public land-use records to find an underserved spot: Prince Street in Nolita. “I can’t think of any other bookseller that did that level of research and thinking before she opened her first bookshop,” Paul Yamazaki, the chief buyer for San Francisco’s famed City Lights Bookstore for nearly 50 years, told me. Books are a notoriously thin-margin business: They are the rare commodity that comes prepriced, meaning there is little flexibility for retailers. But McNally was undaunted. “She’s one of the first of a new generation of very aware readers who wanted to open bookshops and understood the challenges that they were walking into,” said Yamazaki. “In my generation, we were avid in so many senses as readers, but as small-business people, we were very naïve.”

In 2004, the popular wisdom was that bookselling (and maybe even books themselves) was endangered, hopelessly out of step with a digitizing world. Even the superstores weren’t faring well; Barnes & Noble was closing city locations, and Borders filed for bankruptcy in 2011. Neither scale nor niche seemed a guarantee of success. Michael Cunningham, the Pulitzer-winning author of The Hours and one of McNally’s closest friends, told me, “I remember thinking, Oh, good luck to you, you poor fool. It was difficult to imagine a more noble but doomed enterprise than opening an independent bookstore at that point.”

McNally Jackson was a shoestring affair; early employees did anything and everything. “There were not, like, crowds fighting to get into the store,” Jackson said. The first staff hired were all friends or acquaintances — writers and publishing-industry refugees. (Jackson continued to edit and never had a formal position at the shop.)

No one goes into bookselling intending to make a fortune; for McNally, staying afloat was enough. And yet despite the punishing margins, the store was profitable early on — “modestly,” as she put it. “I thought it would survive,” she said. “I thought that was as high as it would go.”

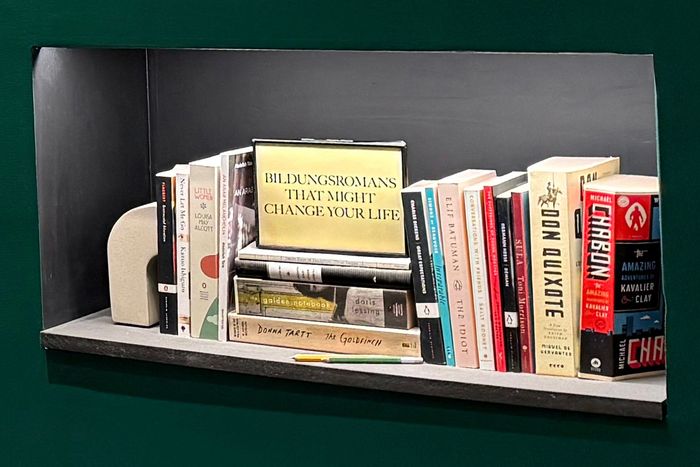

There was very little about the bookstore business that McNally wasn’t ready to rethink. As the years went on and more stores were built, she insisted that they have seating, not just for customers to actually read the books but chaises longues to stretch out on. They would have book groups, dozens of them: Community was the thing, more important even than sales. Contrary to prevailing wisdom, she jammed the stores with books, prioritizing shelf space over display space. Bookseller training at McNally Jackson now specifies that books should be placed on the shelves loosely enough that one can be removed as easily as “the petal of a rose.”

Last winter I started attending one of McNally’s book groups — a public one, held for free at her store in Downtown Brooklyn. (McNally told me, with a laugh, “If we charged for them, I’d have to prepare.”) Once a month, for an hour or two, six or seven strangers, mostly women, would gather around a big wooden library table in an open space on the second floor — the nonfiction section. McNally sat at the head of the table, more TA than professor — not exactly of us but among us. The meetings seemed to draw out her most earnest self. At one point, after several members confessed they had actually put down their phones to plow through Middlemarch, McNally sat back with a satisfied smile. “My life’s work is maybe done,” she said.

McNally asserted the contemporary resonances of the novel — one of her favorites — though she seemed to be someone on whom contemporary resonances are often lost. During a debate about whether Dorothea and Casaubon, the novel’s young heroine and the desiccating pedant she marries, have sex on their honeymoon, someone said, from across the table, “I felt like Lydgate was a fuckboy in New York City.” “I’m older than Casaubon,” McNally replied. “You have to explain that to me.” (One of her employees told me that, during a discussion about Britney Spears’s best-selling memoir, McNally either had or affected no idea who Britney was.)

“Masterpieces can be fun. That’s the takeaway here,” she insisted at one point, her voice rising. The meetings seemed like they served a private purpose for McNally. “I think Sarah lives with so much feeling she doesn’t know how to metabolize it,” said her friend the writer Maria Popova. “Every artist’s art is their coping mechanism. The book clubs give her so much joy. I haven’t seen somebody so animated by a thing that could be so uninspired.”

From day one, McNally did all the frontlist buying — that is, new releases — herself, and she still does. But she also broke with tradition by prioritizing what publishers call the backlist, older books that can form the long tail of sales but are more expensive to stock and less predictable than best sellers, as well as international authors and small-press titles often absent elsewhere. When, for instance, Young Kim, Malcolm McLaren’s widow, self-published a memoir of her erotic, erratic relationship with the punk poet Richard Hell, McNally was one of the few places you could actually count on finding a copy. “All of the stores have to reflect my taste,” McNally said. “Even if it’s wrong.”

But it wasn’t really the wide selection that drew shoppers to McNally’s stores. Most of what she stocked, and everything she didn’t, remained available on Amazon, often for less. McNally had a vibe, a brand. If a Strand tote marked its wearer as an old-school city dweller, a McNally bag — increasingly ubiquitous as the years went by — had a cachet of its own, signaling membership in a stylish reading community that was unrepentant about both the reading and the style. Where the Strand’s charm was that of a dusty attic library, McNally’s was that of a gleaming pied-à-terre with the towering but orderly bookcases of a Dwell spread. Displays were in voicey, overliterate millennialese (“Books That Captured Their Zeitgeist Like a Fly in Amber,” “Our Favorite Smut”).

“It had this bougie aesthetic that attracted a lot of people,” said Justin Torres, who worked as a McNally bookseller before turning to writing full time. (His second novel, Blackouts, won the National Book Award in 2023.) “David Bowie would come in. Whoopi Goldberg came in and bought a ton of books while I was there. It definitely had a reputation.” McNally had a reputation herself. She was a striking figure on the literary scene and half of an emerging power couple: Jackson was becoming known as the industry’s preeminent editor of Black authors.

McNally remained a fixture at the stores; for years, unlike most owners, she insisted her managers put her on the weekly work schedule, and she would often restock shelves herself, befriending and gossiping with her staff, hopping back and forth over a blurry line between employee and employer. Bookselling is often a transitory profession — something done while you finish school, or write your novel, for which your glamorous, capricious boss might be an irresistible character. Nina, the narrator of True Love, a 2020 novel by the former McNally bookseller Sarah Gerard, takes a job at a downtown bookstore whose owner “is a few years older than I am, tall and ethereal like Gwyneth Paltrow. Her name is also Nina, but she’s obviously a superior breed of Nina.”

McNally, though deeply charismatic, could be volatile; adoring but also remote. “I’ve learned she has poor boundaries for an employer,” Nina in True Love goes on. “She may be my friend, or she may be my mentor, or she may be my rival — it changes day to day as different book-sellers fall in and out of her favor. She’s the Regina George of intelligent retail.”

McNally “was definitely a character,” Torres told me: smart, bewildering. She was extremely conscious of the impression she might be making on others. “I wore these Chelsea boots one day to work,” he said. “She complimented me on my boots and was like, ‘Oh, you’ve got big feet!’ It was a nothing interaction. Two weeks later, she said, ‘You know, I was talking to my therapist about what I said about your feet. And I’m sorry.’”

For much of McNally Jackson’s existence, it was McNally Jackson singular. But “the ambition, I think,” Jackson said, “was always for something bigger than just one cute store.” As McNally’s home life became more complicated — she and Jackson divorced in 2010 — so did her work life. In 2013, she opened Goods for the Study around the corner from the Prince Street store, a stand-alone shop selling stationery and the kind of writerly accessories she loved. If McNally Jackson was pitched at bougie readers, Goods for the Study, with its cases of fountain pens, catered to bougie writers or those who might like to become them.

Some business owners considering a second store would opt for something turnkey-ready; not McNally. The space on Mulberry Street was originally in “horrible condition — like really, really bad,” said Sandeep Salter, McNally’s partner in the store. Salter was herself an unusual choice: A McNally bookseller, she was all of 24 years old at the time, she occasionally babysat for Jasper, and she had no capital to contribute. Still, when she proposed that McNally make her a profit-sharing partner, McNally accepted. Within a few years, the two parted ways, splitting their business interests. Salter took the art gallery they’d founded next door to Goods for the Study and moved it to Brooklyn; McNally, the Goods. McNally opened a second Goods for the Study in 2016, on West 8th Street, and, two years after that, a second bookstore in Williamsburg.

McNally’s employees, however, were not feeling the success. Unsalaried, hourly wage bookselling is a lofty pursuit with decidedly terrestrial economics, and entry-level pay for booksellers hovers around minimum wage. (This past holiday season, McNally Jackson was advertising jobs at $17 an hour. The city’s minimum wage at the time was $16.) One McNally manager told staff, “Every independent bookstore that I’ve worked at, there are people who strip at night to make ends meet”; McNally Jackson was no different.

One former McNally bookseller recalled, “I went to go get a matcha a block away, and they were starting at several dollars an hour higher than we were getting. There was a minimum-wage hike at some point, and I remember Sarah openly complaining about how that was going to fuck over the business, that she couldn’t afford it.” (McNally doesn’t remember this.) It didn’t help matters when employees discovered she was buying a Fort Greene brownstone for $2.5 million. Or when McNally announced two new shops: a Seaport store, which opened in the summer of 2019, and another in Brooklyn’s City Point, alongside a Target and a Trader Joe’s.

At the end of 2019, the staff at all five stores voted to unionize. Their complaints echoed what Gerard would later fictionalize: “Favoritism is a problem at our workplace,” they wrote. The unionization process was contentious, and McNally admits to being personally hurt. “I really felt part of that team,” she told me. “I love those people — I thought we were one. To realize that they were talking behind my back — it was almost like high school.”

The two sides argued over the bargaining table until early 2020, when the pandemic nearly scuttled the entire issue: McNally had envisioned her stores as community centers. Now there was no community to fill them. But she wasn’t ready to give up. The company furloughed the majority of its employees, going from a staff of 100 to 15. Previously, McNally Jackson had a very minimal web store. Now that was all there was, and her remaining staff worked to build its infrastructure as McNally drove the family Prius among the shops to pick up, package, and ship the orders herself.

McNally Jackson made it through the pandemic, and staff was rehired as the stores reopened. The union contract was ratified in 2021. The Downtown Brooklyn store had opened in 2020, and the one at Rockefeller Center followed in 2023. McNally negotiated a new kind of lease for these locations: Instead of a fixed payment each month, the amount was tied to sales. This arrangement, in mixed-use complexes, suited both landlord and tenant. Developers enjoyed the halo effect McNally stores had on their surroundings, even at such sterile environs as La Guardia Airport (McNally has a small store there, managed by Hudson News), and McNally was financially protected from bankers and landlords. It was a lesson learned from experience. She’d left the original Prince Street space after a protracted and public feud with her landlord over rent increases — originally from $350,000 to $850,000 a year. Her first shop still sits empty and derelict; graffiti has crept up its grates. McNally walks around the block to avoid it.

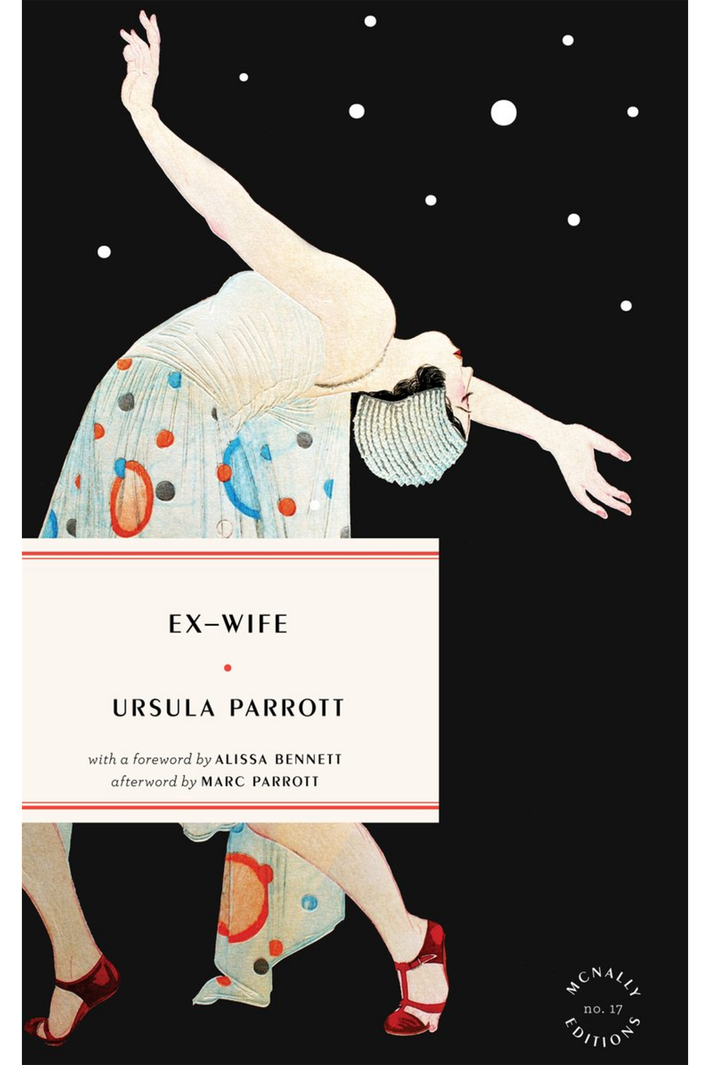

One of McNally’s pandemic projects was the launch, in 2022, of McNally Editions, an imprint of carefully chosen reissues — long-forgotten popular favorites (Ursula Parrott’s Ex-Wife, a surprisingly modern divorce narrative that was a scandal in the 1920s) and alt-classics that had fallen out of circulation (Michael W. Clune’s heroin memoir, White Out). These are books your savviest friend might slip you, and several have gone on to outsize success — Ex-Wife sold some 16,000 copies. The imprint was conceived and pitched by Lorin Stein, and she hired him to edit it, a controversial move. Stein, the former editor of The Paris Review, had stepped down in 2017, apologizing for inappropriate behavior toward female colleagues and writers. Some McNally Jackson staff were unhappy with the hire, considering it a flat-footed move. McNally acknowledged their complaints without changing her course. Stein is now one of three editors working on the imprint, and he keeps a low profile; Nathan Rostron, its associate publisher, has become its public face. But several former McNally Jackson booksellers I spoke with — none of whom wanted their names on the record, fearing McNally’s influence — mentioned Sarah’s habit of championing ostracized men. “I don’t know why I’m like this,” she said by way of response, laughing. “I think I might take a more kind of European approach to justice.” Stein, she said, was “definitely guilty” of misconduct, but he hadn’t deserved permanent exile. (Stein declined to comment.)

In 2022, McNally appeared as a character witness in the civil rape trial of the filmmaker Paul Haggis, a friend. Her testimony amounted to the recollection of a single incident: He had once attempted to kiss her, she declined, he took it sportingly, and they played a game of backgammon instead. (Haggis ultimately lost the case and was held liable to the tune of $10 million.)

It was a few months into our conversations when McNally told me that she herself had been the victim of an assault, which occurred shortly before she testified in Haggis’s trial. The attack was in her apartment: A burglar followed her inside after she walked the dog. As her 13-year-old son slept in his bedroom, the man strangled McNally into unconsciousness in order, she believes, to rape her. McNally awoke to find the man gone and her son looking confusedly out the window. “He doesn’t remember what happened,” McNally said, “but his knuckles were abraded.”

Although the man was found and arrested within days, the event was profoundly destabilizing. She showed up for drinks with a close friend, the writer Sloane Crosley, downplaying the bruise marks still around her neck. (Crosley wept when she saw them.) When I told her I was sorry for what had happened, she replied, “I’m sorry for him too. The whole thing is just fucking awful.” She related the episode with unnerving composure. She seemed to see the situation in novelistic terms, as if the two were characters meeting on some equal plane. She had learned some of the assailant’s story. “When that man broke into my home, days out of Rikers, conspicuously miserable and desperate, with a criminal record indicating mental health problems,” she wrote me, “he and I were (in a scary, sad, violent way) in community.”

In September, McNally and I were emailing when I learned of the latest development in her growing empire. She would open another stationery store — in time for Christmas, she hoped — and act as her own contractor. “I’m so often at contractors’ mercy,” she wrote. “What degree of expertise is needed? Is it like hiring a project manager? A neurosurgeon? I’m going to find out.”

For years, McNally had an unusual degree of involvement in every aspect of her business. She acknowledged that, before the union contract, the personal and the professional had become muddied; she had, for example, been granting raises on an ad hoc basis, a gesture she said she intended to be benevolent but that had undermined equity. She also acknowledged her particular intensity: McNally is currently pursuing a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. “I’m pretty sure,” she said. “I really value specificity, to a point which I think has made me good in some ways. But then also it makes me fixate sometimes in ways that I wonder if it’s annoying for people I work with.”

As McNally Jackson grows, so does its influence. McNally is quick to point out — and other independent booksellers agree — that where bookshops are concerned, a rising tide lifts all boats. When Jessica Stockton-Bagnulo, a former McNally events director, broke off to found Greenlight Bookstore in 2009, McNally was supportive. Even so, she is a rare presence at local indie-bookseller events. At a recent gathering, “I actually was slightly surprised to see her,” Stockton-Bagnulo said, quickly clarifying that she meant it in a positive way — McNally has a high-school popular-girl aura. “She’s very beautiful, and she’s very stylish, and, you know, she comes from a background that not all of us come from,” Stockton-Bagnulo said. “So I think there is in some sense a little bit of, like, an awe.”

McNally’s atmosphere has become a bit more rarefied. While she remains close to the indie-bookworld people she has known for years, she has become pals with James Daunt, the turnaround CEO of Barnes & Noble, who began as an indie bookseller (Daunt founded and still owns Daunt Books in the U.K.). Daunt is admiring of McNally and her stores, and it hasn’t escaped notice that Barnes & Noble’s redesigned stores have taken on a McNally-ish aspect. “Barnes & Nobles now look exactly like McNally,” said Lisa Lucas, McNally’s friend and the former director of the National Book Foundation. “Shockingly like.” The new Barnes & Noble on Atlantic Avenue has the blond wood and chatty displays of a McNally Jackson, albeit with the same old B&N best sellers in the window. “It reeks of algorithm,” Doug Singleton, McNally’s longtime director of operations, sniffed.

The signal difference between Barnes & Noble and McNally, besides their David-versus-Goliath sizes, is that McNally has always been the sole owner. (B&N, on the other hand, is owned by private-equity firm Elliott Management, which took it private in 2019 for $683 million.) She is — she perhaps has the freedom to be — untroubled by lust for profit. The McNally Editions imprint, despite the positive press, made a mere $10,000 last year.

By December, McNally’s new store was nearing completion — mostly. “It’s hell,” she said, popping out of a doorway on Broadway near 73rd Street. She surveyed the building site, inside the Ansonia, in boot-cut jeans, triangulating between her painter (a former McNally employee), a drywalling crew, and a team installing the fire alarm. “I’m a terrible contractor,” she said, laughing.

Over lunch nearby, she promised this store would be her last. “I’m turning 50, and I really want to step back and regroup,” she said. “I want to do something a little more ostentatious, more truly helpful.” She plans to build a network of book clubs and what she called “reading festivals” with featured speakers — “Imagine a Broadway star, an art auctioneer, a professor, and a real-estate agent discussing Ovid, slowly, deliberately, respectfully.” (She is in fact now ruminating on another bookstore, also for the Upper West Side.)

I asked her if there was any connection between her assault and her intensified focus on community and watched the wheels begin to spin. We’d been picking at plates of Mediterranean food, and she stopped. “When you say that, I immediately start imagining doing groups around like — like rape and rape survivors,” she said.

I paid the check, and we parted ways. Two weeks later, an email arrived. “I think there is something very interesting in your theory,” she wrote. “I don’t know if this was a professional turning point for me. It’s hard to experience one’s own life in such a linear way, but I have since decided that the next half of my working life will be devoted to making safe community spaces. I have started reaching out to community partners to form survivors book groups and writing groups.”

One of the things McNally loved about her discussion groups, she had told me at our lunch, was their deep shared space. She maintained an almost childlike belief in their power. There seemed to be no problem so dark that books couldn’t be prescribed. The clubs, she said dreamily, “are my favorite thing. You don’t have to make small talk at all.”