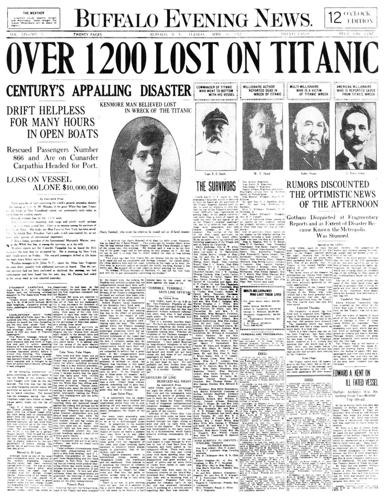

This story was originally published in 2012 on the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic.

On a clear April night a century ago, two men from Western New York retired to accommodations aboard R.M.S. Titanic that were as different as the lives they led by day.

Edward Austin Kent, 58, a wealthy architect, was in Cabin B-37 in the first-class quarters of the ship, an elegant room near the starboard bow not far from the gilded "millionaires' suites."

Henry Sutehall Jr., 25, a tradesman and musician, slept in a small bunk in Third Class - among many hundreds of immigrant families headed toward new lives in America.

Like many of the 2,200 others on board, Kent and Sutehall had set sail on the Titanic with pleasure and optimism. Kent was headed back to Buffalo after a professional trip abroad. Sutehall was bound for Kenmore to be reunited with his family after a long absence.

People are also reading…

Late on the night of April 14, 1912, when Titanic scraped an iceberg in the North Atlantic, damaging its starboard bow and causing the ship to founder, Kent and Sutehall would have been among the earliest to know.

Kent may have been among those well-to-do passengers who noted ominous chunks of ice on the upper decks.

Sutehall's berth near the ship's hull meant he would have felt the jar of the impact more than others. Soon, all aboard would know what happened. By 2:20 a.m. on April 15, the storied ship - the stuff of legend and myth, even on its maiden voyage - had disappeared beneath the ocean waves, some 400 miles off Newfoundland.

Like most men in first class, Kent never took a seat in a lifeboat.

In Third Class, Sutehall had even less of a chance at survival.

The two men, along with 1,500 others, perished in the frigid waters of the Atlantic, 100 years ago today.

This is their story. Like the Titanic itself, it begins in hope and possibility, and ends in tragedy so grandly scaled it still inspires awe.

Before April 14, 1912

If Edward A. Kent and Henry Sutehall Jr. ever met, there is no record of it.

Kent, the scion of a prosperous Buffalo family, lived in the comfort generated by his family's wealth, much of which came from their department store, Flint & Kent. The store, located in the 500 block of Main Street, catered to generations of Buffalo's gentrified classes, offering silk petticoats, pricey hosiery, and "Fine Furs at Cost."

"It was a department store for the carriage trade," recalled one of Kent's descendants, an elderly woman who asked that her name not be disclosed out of a wish to avoid attention. "I don't mean it was a fancy place, but they sold quality goods."

Kent was 58 in 1912, and a perpetual bachelor. "He lived at the Buffalo Club [on Delaware Avenue]. Back then it was much smaller, and people used to live there," said the Kent relative.

Kent received the best of educations, first in Dr. Horace Briggs' Boys' Classical School in Buffalo and then at Yale University, where he graduated in 1875 with a degree in civil engineering from the Sheffield Scientific School.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Kent built a well-regarded architectural business in Buffalo, working on many projects with his brother William. He designed Temple Beth Zion on Delaware Avenue, the Chemical No. 5 fire house on Cleveland Avenue, and the Flint & Kent building. With William, he conceived the mosaic design of the tile floors in Ellicott Square.

In the early 1900s, the Kent brothers designed the imposing structure that would become the Unitarian Universalist Church of Buffalo on Elmwood Avenue. The massive limestone building, with its arching oak beams and lofty ceilings, won Kent high praise. "Of the many beautiful churches in this city, there is not one more beautiful, more artistic and original in design, than the recently built First Unitarian Church," the Buffalo Express newspaper raved, when the church was opened in 1906.

"He was really cutting-edge," said Bill Parke, the church's historian, while giving a tour of the space Kent designed. "To be able to do this (church) building, the Chemical fire house, the Flint & Kent building, these great shingle-style houses downtown - I don't even know fully how one of these buildings works, let alone all of them."

By early 1912, Kent was ready for a trip abroad. He embarked on a two-month professional tour of Europe, where he was described as a consummate gentleman by those who met him.

By April 10, however, Kent was ready to return to Buffalo. He had booked passage on the brand-new luxury liner of the White Star line that was the talk of two continents.

In Cherbourg that day, wearing his family ring -- a gold band bearing the Kent crest -- Kent was likely feeling pleased at a job well-done when he boarded Titanic.

***

If Sutehall, known as "Harry" to his friends and family, ever encountered Kent during his youth, it likely would have been inside that Elmwood Avenue church.

According to Sutehall family lore, Harry's father, Henry Sr., a skilled plasterer who specialized in fancy techniques, worked on the church interior as it was being built.

"He did this fancy scrollwork plastering," said Bob Sutehall of Angola, who is Harry's nephew. "His work is in some of the fanciest churches in Buffalo - Father Baker's church [Our Lady of Victory Basilica], another one on Delaware Avenue that was torn down. He had his bifocals ground the opposite way, with the bifocal part on the top, because he was always looking up at his plaster."

If a proud Henry Sr. ever took his son to see his craftsmanship in what was then the First Unitarian Church of Buffalo, then perhaps - no one knows for sure - Harry and Kent first met in this pleasant sort of way.

In many ways, the Sutehalls were far removed from the world Kent lived in.

The family had emigrated to the United States from England in 1895, when Harry was 9 years old. Henry Sr. and Sarah Sutehall had five children and settled in Kenmore, moving into a house on East LaSalle Street as the family grew. Sarah Sutehall would work to support the family, too, with a confectionery shop and ice-cream parlor - known as Mrs. Sutehall's - that stood on Delaware Avenue in the village.

Sutehall, as a young man, already displayed the wit and sense of fun that would characterize his adulthood.

In one family photo, Sutehall clowns around at a washtub, clad in an apron, his shirtsleeves rolled up. He is pretending to do the family washing. Nearby stands his mother, Sarah, who has her hands on her hips in mock annoyance.

In the photo, Sutehall wears his trademark lopsided, charismatic grin.

"That was a family trait," said Ellyn Sutehall, Bob Sutehall's wife, who with him has studied the family's genealogy. "They had a really good sense of humor, all of them."

The family also shared a love of music, playing instruments together and filling the Kenmore home with the sound of waltzes, reels and popular tunes.

As he grew older, Sutehall was a carriage-trimmer, which meant he did finish work on the bodies of carriages, sleighs and early motorcars.

But Sutehall didn't want to work with his hands forever; and he wanted to see a bit of the world.

Which is why, in 1910, Sutehall and a close friend, Howard Irwin, decided to embark on a trip around the world. Sutehall left Buffalo, a relative recalled, with "$50 and his violin." The pair planned to make their way by picking up work where they could, either as musicians or tradesmen.

For a time, it worked. The two young men saw much of the United States, as well as parts of Canada, Australia and Europe. By 1912, Sutehall and Irwin were in England, and ready to return home.

For some reason that has never quite been explained - some people say Irwin went to visit a former flame; more far-fetched theories posit he was abducted while in a London tavern - Irwin and Sutehall did not make the final leg of their journey together.

Irwin sailed separately back to America. Sutehall thought himself luckier than his friend, for he had landed a ticket for the maiden voyage of Titanic.

April 14, 1912

That Sunday evening, April 14, Sutehall and Kent passed the time in very different circumstances aboard the ship.

Sutehall, in steerage, would have eaten simply: ragout of beef with potatoes and pickles, currant buns, bread and butter, apricots and tea.

"The evening meal (in steerage) was a sort of tea," said Hugh Brewster, author of the new book "Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World." "Dinner was served as lunch in third-class - a class difference."

After his meal, Sutehall would likely have spent some time in one of the common rooms provided for third-class passengers, many of them immigrants. There might have been music and dancing - something Sutehall may have joined in.

Then, he would have retired to a small berth in a tiny room he would have shared with a few other men.

"There were far more people in third class than in first and second class put together," said Brewster, who has written or edited more than 20 books on the disaster. "That's where the money (for the shipping line) was, in transporting immigrants."

There was strict policy on board the Titanic against passengers mingling with others in different classes. Kent and Sutehall would not have encountered one another, Brewster said.

"They wouldn't have talked or met. Not even during boarding -- they boarded at different times, and they boarded through different gangways," said Brewster. "It would be very hard to imagine them ever meeting at all."

Kent, for his part, would have dined in luxury that evening in the first-class dining saloon, with the wealthy, cultured friends he had made on board. ("Our Coterie," they called themselves.)

"People said it was like an elegant hotel," said Brewster.

Kent's meal spanned 11 courses, and included choices of oysters a la russe, poached salmon with mousseline sauce, filet mignon, lamb with mint sauce, roast duckling, roast sirloin of beef, roasted squab, asparagus salad with champagne sauce, and pate. For dessert, diners were served Waldorf pudding and "chocolate-painted" eclairs with French vanilla ice cream.

Afterward, Kent enjoyed conversations with his friends, such as Mrs. Helen Churchill Candee, a 53-year-old society woman and writer with whom he had been spending a good deal of time on board. They talked of mutual interests such as antiques and interior design, Brewster said. "They would have had a lot in common," he said.

The ship had been at sea for four days. Passengers were thinking ahead to New York - and to reuniting with family and friends.

11:40 p.m. -- 2:20 a.m., April 14-15, 1912

After Titanic struck the iceberg, at 11:40 that night, passengers in all classes had two hours and 40 minutes to see how their lives would play out.

Kent had been in bed in his starboard cabin and would have been roused by a crew member or the noise of activity on the decks.

Shortly after midnight, Kent would run into his friend Mrs. Churchill Candee, who was about to board a lifeboat, Boat 6.

The society woman asked Kent to hold onto two of her personal possessions, a silver flask and a portrait miniature of her mother.

The portrait was a prized possession of Churchill Candee's. Kent promised he would keep the treasures safe. Then he ushered his friend into a lifeboat and stayed on deck with the other men in first class.

In third-class, meanwhile, Sutehall, with others in third class, would have been locked into the lower decks by the ship's crew. For most of the next several hours, they would be forced to stay below decks, where there was little chance of survival.

But there was little chance for men in general. Most of the lifeboats - many not even full - were being sent out with women and children only.

And, as the Sutehalls in Angola note, the ship was gravely undersupplied with lifeboats - having just 20, or enough for perhaps 1,200 people, roughly half of what was needed.

"As the story goes, they were forcing the steerage people back into the ship, because they didn't have room," said Bob Sutehall.

By 2 a.m., in any case, the lifeboats were all gone.

And, at 2 a.m., men from third-class - like Sutehall - were at last allowed up on deck.

The ship soon would sink, in spectacular fashion, its stern rising into the air, exposing its propellers to view, then plunging like a shot arrow to the bottom of the ocean, 2 1/2 miles below.

In these final minutes, Kent and Sutehall - so long separated by circumstances of birth and station - were brought together on those crowded decks of the Titanic, now listing dangerously and taking on water.

Perhaps they met one another, as the waters rose and the ship tilted precariously.

Perhaps they realized they shared a hometown.

Perhaps they shook hands, even embraced.

Kent, still wearing his gray overcoat, his dress suit pants, and his gold Kent family signet ring, would be one of the few victims - just 324 of the 1,500 lost - whose bodies would be recovered after the shipwreck.

Sutehall's body was never to be found.

After April 15, 1912

The sinking of Titanic is viewed as one of the most important events of the past century. The sinking of the "unsinkable" ship, the most opulent and largest moving machine in the world in its time, fascinates people in both its historical detail and its rich symbolism.

"It's become our most potent modern parable," said Brewster, the expert in Toronto. "It fascinates everybody, young and old. We don't have many metaphors left. ... It's something everyone understands."

In a way, the fates of Kent and Sutehall were typical of most of the men aboard the legendary ship.

Of Titanic's passengers, just 20 percent of the men on board would survive, compared with nearly 75 percent of the women, Brewster notes in his book. Men in steerage fared far worse than any others.

But Kent and Sutehall both lived on, in the days and years after the Titanic disaster.

When Kent's body was recovered, by a rescue ship, Mrs. Churchill Candee's silver flask and portrait miniature were still in his pockets. Both items were returned to her. In 2006, the miniature was sold at auction in England for a record sum.

Kent was buried in Forest Lawn in Buffalo, where the inscription on his tombstone does justice to his nobility in helping others to safety while knowing he himself would die:

"Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends."

As for Sutehall, his family slowly gave up hope that he would be found. They held a memorial service for Harry in their Kenmore home several weeks after the disaster.

"A lot of the dead were buried in Halifax. There are graves there, but they are marked 'Unknown,' " said Bob Sutehall. "So we don't know."

But Sutehall's story was not yet concluded.

Two years after his death, his mother in Kenmore received a letter and a package. It had come from Australia, from a small town, Tempe, where Sutehall had worked for a time while in that country - and where, Sutehall family lore has it, he met a young woman that he had fallen in love with, become engaged to, and planned to bring to America to marry.

In the 1914 letter, the writer, R.H. Allcock, an Australian friend of Sutehall's, expressed condolences to Sarah Sutehall. He sent along a memento of her son: a silver locket, containing a small photo of Sutehall taken in Australia and a lock of his thick, dark-brown hair.

The man wrote that Harry Sutehall had clipped the lock of his own hair with some friends as he was leaving Australia -- and tacked the hair, and an English penny, over his work station in the Tempe business.

Maybe he did it for luck, or maybe as a token of remembrance.

Whatever the case, Sutehall couldn't have known how telling his act would be.

For, on the wall above the English penny and the lock of hair, Harry Sutehall had written in jest the following words: "In Memory of H. Sutehall."

*****

Note on this story:

Material for this report was gathered in many ways and from a variety of sources. Newspapers and books from 1912 were consulted for the details of the night of April 14-15, 1912. Interviews were conducted with family members and descendants of Henry Sutehall and Edward A. Kent, as well as with historical researchers and archivists at Yale University and the Unitarian Universalist Church of Buffalo, where historian Bill Parke has studied Edward A. Kent; local researcher Edward Dibble helped with genealogical and other research. Hugh Brewster's book, "Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World" was useful in piecing together the narrative of Kent and Sutehall.