Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III aced the test for his former University of Virginia law professor, A.E. Dick Howard, with a 4th U.S. Court of Appeals ruling this week on the constitutional showdown between President Donald Trump and the federal courts over the deportation of a Maryland man to a prison in El Salvador without due process of law.

“It is difficult in some cases to get to the very heart of the matter. But in this case, it is not hard at all,” wrote Wilkinson, who President Ronald Reagan nominated to the court in 1984.

“The government is asserting a right to stash away residents of this country in foreign prisons without the semblance of due process that is the foundation of our constitutional order. Further, it claims in essence that because it has rid itself of custody that there is nothing that can be done.”

“This should be shocking not only to judges, but to the intuitive sense of liberty that Americans far removed from courthouses still hold dear.”

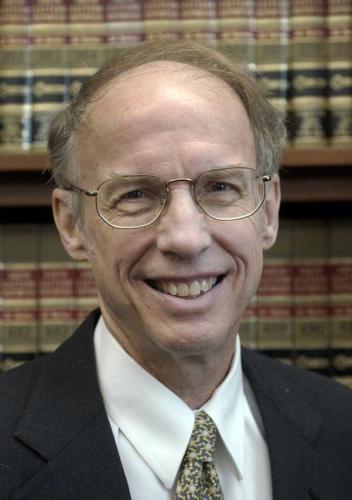

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals is seen in 2014. Wilkinson said the Trump administration's assertions in the case involving Kilmar Abrego Garcia "should be shocking."

Howard, who led the last revision of Virginia’s constitution more than a half-century ago, has known Wilkinson as a student, a research assistant, a law school colleague and a federal appeals court judge for more than 50 years. He called the seven-page ruling “one of the finest opinions Judge Wilkinson has ever written.”

“It’s really a classic opinion,” the retired legal scholar said on Friday. “This opinion should really be printed in textbooks.”

Wilkinson, who grew up in Richmond’s West End with a close view of the confrontation between the courts and political establishment over Virginia’s policy of Massive Resistance to school desegregation, grounds the ruling by the three-judge panel in the balance of power between a strong-willed executive branch of government and a judiciary intent on carrying out its own role under the U.S. Constitution.

“The respect that courts must accord the Executive must be reciprocated by the Executive’s respect for the courts,” he writes. “Too often today this has not been the case, as calls for impeachment of judges for decisions the Executive disfavors and exhortations to disregard court orders sadly illustrate.”

The deportation case

The three-judge panel’s ruling denies the Trump administration’s request for a stay of a lower court ruling that requires the government to return Kilmar Abrego Garcia to the United States from a prison in El Salvador. The government mistakenly sent him to El Salvador as part of the president’s unilateral deportation of hundreds of undocumented immigrants whom he contends committed crimes as members of terrorist gangs.

Abrego Garcia came to the U.S. from El Salvador illegally, but a federal immigration judge ruled in 2019 against his deportation because of potential harm at the hands of criminal gangs in his home country. The lower court said it found no evidence to support the government’s accusation.

Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., right, speaks with Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran citizen who was living in Maryland and wrongly deported to El Salvador by the Trump administration, in a hotel restaurant Thursday in San Salvador, El Salvador.

“The government asserts that Abrego Garcia is a terrorist and a member of MS-13,” a criminal gang, Wilkinson writes. “Perhaps, but perhaps not. Regardless, he is still entitled to due process.”

On April 10, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with a lower court that the government must “facilitate” the return of Abrego Garcia, while requiring the district judge to respect the president’s powers to conduct foreign policy.

U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis in Maryland is still trying to enforce the court’s order.

A lawyer for the Trump administration acknowledged in federal court that the decision to send Abrego Garcia to the prison in El Salvador was “a mistake,” but the government has tried to avoid responsibility for ensuring his release and return, or doing anything to make it happen.

In his ruling, Wilkinson acknowledges the president’s powers, but notes: “’Facilitate’ is an active verb. It requires that steps be taken as the Supreme Court has made perfectly clear.”

He also appeals to the president, without naming him, to avoid a constitutional crisis that could wound the executive and judicial branches of government, undermining the balance of powers the nation’s founders established under the Constitution.

“We yet cling to the hope that it is not naive to believe our good brethren in the Executive Branch perceive the rule of law as vital to the American ethos,” the opinion states. “This case presents their unique chance to vindicate that value and to summon the best that is within us while there is still time.”

Virginia roots

The plea reminded Howard, the judge’s former professor and mentor, of President Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address on the precipice of Civil War, when he appealed to “the better angels of our nature” to reconcile the division between North and South to preserve the union.

Howard

“He’s really asking for the executive to give the court due respect,” he said of Wilkinson’s ruling.

The opinion, in substance and tone, came as no surprise to those who have known and worked with Wilkinson. In addition to 41 years on the appeals court bench, he ran for Congress at age 25, wrote editorials for the Virginian-Pilot newspaper in Norfolk from 1979-81, and authored a half-dozen books. Those books include a history of changing Virginia politics under the reign of then-U.S. Sen. Harry F. Byrd Sr., the architect of Massive Resistance, and a memoir of his own experience as a law clerk under U.S. Supreme Court Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., a family friend from Richmond.

“I don’t think he’s an ideologue by any stretch of the imagination,” said Carl Tobias, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Richmond who was Wilkinson’s law school classmate at UVa and a colleague in Howard’s push to revise the state Constitution. “I think he applies the law to the facts as he understands them.”

“He’s a product of the West End,” Tobias said, referring to traditional seat of economic power and social status in Richmond.

Larry Sabato, president of the Center for Politics at UVa, said he first knew Wilkinson as the first student member of the board of visitors at UVa, on which the judge’s father, J. Harvie Wilkinson Jr., also had served.

“I was involved in a movement to get a student on the board of visitors, and they gave us Jay Wilkinson,” Sabato said, referring to the name his old friends call him.

“He’s mainly a conservative, but there’s a libertarian touch to him,” he said.

Tobias, his former classmate, said he was struck in the opinion by Wilkinson’s invocation of President Dwight Eisenhower, who ordered federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957 over the objections of then-Gov. Orval Faubus to enforce the Supreme Court decision outlawing governmental racial segregation of public schools.

Wilkinson writes, “President Eisenhower honored the ‘inescapable’ duty to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education II to desegregate public schools ‘with all deliberate speed.’”

“It was a great stroke,” said Tobias, who grew up in Petersburg amid the turmoil over school desegregation.

Wilkinson had a personal perspective on the clash between political and judicial imperatives in Richmond during Massive Resistance. He attended St. Christopher’s School, a private boys school in the city’s West End. His father was chief executive of what was then State Planters Bank and Trust Co. (a predecessor of Crestar and now Sun Trust Bank), and a close friend of Powell, the future Supreme Court justice who was then a lawyer at Hunton & Williams law firm and chairman of the Richmond School Board.

The elder Wilkinson and Powell were part of a group of businessmen concerned about the effects of Massive Resistance on Virginia’s economy, who sought to persuade then-Gov. J. Lindsay Almond to abandon the policy and allow desegregation of public schools.

Wilkinson’s father “was one of the voices who really quietly behind the scenes tried to bring Virginia out of the period of Massive Resistance and into the modern age,” Howard said.

It is Powell’s voice that Howard says he hears in Wilkinson’s writing in the Abrego Garcia opinion.

“The way Judge Wilkinson thinks about public affairs, the way he thinks about the law, the way he thinks about judging reminds me of Justice Powell,” the UVa scholar said. “Justice Powell was a measured voice of reason on the Supreme Court.”

Sabato said, “He’s exactly a Lewis Powell type.”

Wilkinson almost followed Powell to the high court. He was on President George W. Bush’s short list of potential nominees in 2005 to succeed ailing Chief Justice William Rehnquist, but Bush chose John G. Roberts Jr., now chief justice of a court that Trump is pushing to uphold his prerogatives.

For Tobias, at the University of Richmond law school, the Abrego Garcia case represents a test of the constitutional balance of power that his old UVa classmate tries hard to resolve.

“He’s not sure how it will work out,” he said of Wilkinson, “but he’s going to do everything he can to make it work out.”

VIDEO & PHOTOS: Statue of segregationist Harry F. Byrd Sr. removed from Capitol Square in Richmond

The statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former Virginia Governor and U. S. Senator, lies on a flatbed truck in front of the new General Assembly Building under construction after it was removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond, VA Wednesday, July 7, 2021. The General Assembly approved the removal during the last session.

The statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former Virginia Governor and U. S. Senator, is lowered onto a flatbed truck in front of the new General Assembly Building under construction after it was removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond, VA Wednesday, July 7, 2021. The General Assembly approved the removal during the last session.

The statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former Virginia Governor and U. S. Senator, lies on a pallet after it was removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond, VA Wednesday, July 7, 2021. The General Assembly approved the removal during the last session.

The statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former Virginia Governor and U. S. Senator, is removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond, VA Wednesday, July 7, 2021. The General Assembly approved the removal during the last session.

A workman looks at the statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former Virginia Governor and U. S. Senator, lying on a pallet after it was removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond, VA Wednesday, July 7, 2021. The General Assembly approved the removal during the last session.

Workmen secure the statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former governor and U.S. senator, to a pallet after it was removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond on Wednesday. The General Assembly approved the removal during the last session.

Del. Jay Jones, D-Norfolk, left, talks with Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, right, before the statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former Virginia Governor and U. S. Senator, background, was removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond, VA Wednesday, July 7, 2021. The General Assembly approved Jones' bill calling for the removal during the last session.

Del. Jay Jones, D-Norfolk, left, and Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, right, make a statement to the media before the statue of Harry F. Byrd, Sr., former Virginia Governor and U. S. Senator, background, was removed from the pedestal in Capitol Square in Richmond, VA Wednesday, July 7, 2021. The General Assembly approved Jones' bill calling for the removal during the last session.

Jones