Lions, bulls and dragons: Robert Koldewey and the discovery of Nebuchadnezzar II’s Babylon

Koldewey's excavations led to the recovery of over 5,000 Babylonian tablets and an overview of what was once the great ancient Babylon.

13 MAY 2025 · 10:25 CET

“Is not this the great Babylon I have built as the royal residence, by my mighty power and for the glory of my majesty?” (Daniel 4:30)

Babylon is a place that evokes different feelings and emotions: longing, frustration, abandonment, sadness.

It is mentioned several times in the Bible; both in the first book, Genesis, and in the last book, Revelation. It is the city where Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) died, in fact, it is the city where Alexander wanted to establish the capital of his empire.

A legacy of Babylonian scholarship is our division of the day into twenty-four hours, with the hours and minutes divided into sixty; that is, sixty minutes and sixty seconds. The Babylonians used the sexagesimal system (base 60 instead of base 10) for their calculations because the number 60 is easy divide by many different whole numbers.

This system was adopted by Greek scholars and eventually applied to the measurement of time. The question that arises is: how is it possible that such an important city in ancient times could have fallen into oblivion?

The search for this city began when Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela (1130-1173) mentioned it in his work, The Book of Travels.

In this book, Benjamin of Tudela recorded the cities he visited in Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt.

He describes the city of Baghdad as follows: It is large: ten miles in circumference around the city. It is a land of palm trees, orchards and gardens like no other in all the country of Shinar. People from all countries go there with their goods, and there are wise men in the city, philosophers who know every kind of science, and magicians who know every kind of enchantment.

He also said that the city of Nineveh was near Mosul, which was proved by excavations carried out by Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894).

The city of Babylon was located in southern modern-day Iraq on the Euphrates River, 89 km from Baghdad.

The city's political status was first established by King Hammurabi (reigned 1792-1750 BC), a king known today for his code of laws. Babylon reached its greatest glory during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BC).

During that time, Babylon was the largest and most important city in the world. Nebuchadnezzar was a wealthy king who never hesitated to demand the best from his architects.

The palaces of Babylon were majestic; in addition to two huge residences in the centre of the city, Nebuchadnezzar and his court could take refuge in a large, well-ventilated ‘summer palace’ in the north, to escape the worst of the heat and smells of the metropolis.

The remains visible on the site today give little idea of the architectural splendour of Babylon, a cosmopolitan metropolis at the centre of a great empire, home to the most magnificent palaces and temples built to show the splendour of the empire.

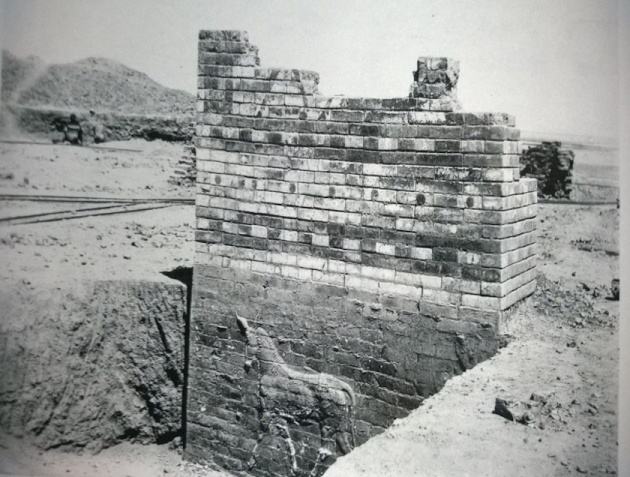

The ziggurat, or stepped temple tower, overlooked the city's skyline, while the great surrounding walls protected the bustling capital. Built of clay bricks, they eventually succumbed to decay and demolition until they were finally lost completely.

Claudius James Rich (1787-1821) was a British agent at the consulate in Baghdad. Rich's historical interest in the place led him to visit what he believed to be ancient Babylon in 1811 and 1817.

Although he was able to collect some cuneiform tablets, his mission was to make a topographical study of the place for future archaeological prospection. Rich died of cholera in 1821, unable to fulfil his dream of excavating at Babylon.

Paul Emile Botta (1802-1870) was commissioned by the French government to explore the north of modern Iraq. There, in 1843, he found the palace of the Assyrian king Sargon II, who reigned from 722 to 705 BC.

Both Paul Emile Botta and Austen Henry Layard used Rich's notes, which included not only the topography of Babylon but also other places in northern Iraq.

Rich's writings were a great asset in the British and French excavations that uncovered palaces, carvings and tablets from the time of Assyrian rule in the area.

Following his success uncovering the city of Nineveh and the palace of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (705-681 BC), Layard decided to excavate in the Babylonian area in 1850-1851.

Despite finding tablets and fragments of bricks bearing the name and titles of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BC), Layard was frustrated that the finds in Babylon were not of the same magnitude as the Assyrian carvings found in Assyria.

French excavators were as frustrated as Layard. In 1851, the French government commissioned Fulgence Fresnel (1795-1855) and Julius Oppert (1825-1905) to undertake an archaeological expedition to Babylon.

Despite finding cuneiform tablets and other artefacts, the expedition ended in tragedy when in 1855 a group of Bedouins attacked the ship carrying the boxes with not only the artefacts, but also the plans and drawings. The ship sank, so that France decided to focus its efforts on other parts of Mesopotamia and the Middle East.

The UK and France competed with each other not only economically but also archaeologically. Both the British Museum and the Louvre sought to fill their halls with objects from the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia.

At the end of the 19th century, Germany decided to join the competition of nations that could fill their museum halls with ancient artefacts.

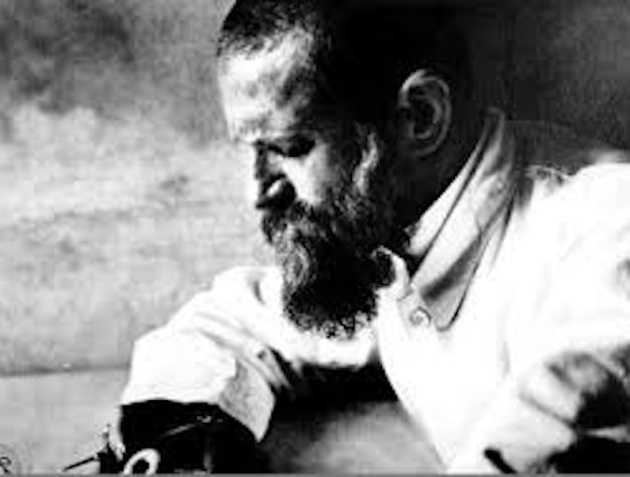

Robert Koldewey (1855-1925) was the ideal candidate to carry out the excavations in Babylon. His uncle Carl Koldewey (1837-1908) had led two German expeditions to the North Pole, showing that the spirit of adventure ran in the family.

Koldewey studied architecture, archaeology and art history in Berlin, Munich and Vienna. These studies were very important because archaeology is closely related to architecture, and he was able to provide architectural plans of the discoveries he made.

Koldewey had already had experience of several excavations. In 1887 he had been to Lagash, an archaeological excavation in the south of present-day Iraq.

That gave him experience in excavations where there were many adobe buildings, which he later applied to excavations in Babylon, where there were also a number of adobe buildings.

“Excavations began on 26 March 1899 from the Kars side north of the Ishtar Gate. On my first visit to Babylon, 3-4 June 1897, and again on my second visit, 29-31 December 1897, I saw numerous fragments of enamelled bricks in relief, some of which I took with me to Berlin”, Koldewey recalled.

“The peculiar beauty of these fragments and their importance for the history of art were duly recognised by His Excellency R. Schöne, then Director General of the Royal Museums, and strengthened our decision to excavate the capital of the Babylonian Empire”, he added.

Walter Andrae (1875-1956) even thought that Koldewey's decisions were guided by “a higher will”, because it was somewhat strange that the English and French had not discovered the monuments that Koldewey had found.

In fact, the reconstructor of the Ishtar Gate in Berlin wrote in his memoirs that the discovery of the Ishtar Gate and the Temple of Esagila was not a matter of chance, but of fate.

The Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft was founded in 1898 with the aim of funding large-scale excavations in the Ancient Near East in order to find monumental sculptures for the Berlin museums. Today, the German Oriental Society aims to promote research in this field and make it accessible to a wider public.

The society was supported by the Kaiser himself and received donations from many wealthy industrialists.

Mesopotamia was of great interest to Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859-1941). When the proclamation of the Weimar Republic in 1918 forced Wilhelm into exile, he settled in the Netherlands and devoted himself to the study of ancient history.

In 1938 he wrote a short essay on Mesopotamian kingship, Das Königtum im alten Mesopotamien, in which he argued that there was an unbroken spiritual line between the Babylonian and Prussian empires and that the stories of Gilgamesh reflected an ideal that he himself had tried and failed to defend: "the idea of a universal monarchy embracing heaven and earth".

German politicians and engineers lobbied to get permission and funding to build a railway from Berlin to Baghdad and from there to Basra.

In 1899, the final agreement was signed between the Ottoman government and the Germans of Kaiser Wilhelm II: mining rights were granted within 20 km of the proposed railway, and excavation included the removal of antiquities, with all the material extracted, including archaeological finds, to be exported to Germany.

Since the route of the proposed railway passed many visible ancient sites, the German archaeologists chose the best locations for their excavations. Among them was Babylon.

A journalist wrote in the Daily Mail on 13 June 1899 that Britain was losing ground in the international rivalry for productive archaeological sites, overtaken by Germany thanks to its alliance with Ottoman Turkey.

Koldewey used the railways to clear thousands of tons of soil. He employed over 200 workers, who took turns to excavate the earth.

Koldewey continued to work at Babylon duringt much of the First World War (1914-1918), as German engineers struggled in vain to complete the Berlin- Baghdad railway.

Excavations ended during the war, in 1917, when the Ottoman Turks withdrew from Baghdad and the British army entered. Koldewey excavated Babylon continuously from 1899 to 1917.

One of the new technological advances that had the greatest importance and impact on the beginnings of scientific archaeology was photography.

In 1839, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) in England and Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) in France developed the process of taking pictures.

Photography grew rapidly alongside archaeology, as it became widely used in archaeological excavations.

Although photography was used as a tool in all sciences, archaeology was the field in which it was most widely used in its early days, a combination of scientific objectives and technological invention.

It is important to mention that Henry Fox Talbot was one of the first to decipher the cuneiform writing. Photography radically changed archaeology and archaeological methods, which had previously relied on drawings and engravings, but never replaced them.

Photographs from the German excavations in Babylon are of particular interest, as they reveal working methods and monuments discovered in the late 19th century. Archaeological photographers had to carry all their equipment and chemicals with them to develop the images on site.

Koldewey's most famous discoveries are the Processional Way and the Ishtar Gate, spectacularly reconstructed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin.

The Ishtar Gate was the largest entrance to Babylon, lined entirely with dark blue enamelled bricks and decorated with carvings of hundreds of parading bulls and dragons, the image that greeted ancient visitors to the capital must have been unforgettable.

Through the Ishtar Gate ran the broad Processional Way, flanked on both sides by carvings of lions.

The bulls were particularly associated with Adad, the god of storms. The dragons, called mušhušššu in Babylonian, are a composite with the head of a snake, the hind legs of an eagle and the front legs of a lion.

Dragons were sacred to the god Marduk, and kings prized them for their power to ward off enemies and evil spirits.

An inscription of the Babylonian king Neriglisar (560-556 BC) reads: “I have thrown seven mušhušššu, which sprinkle deadly poison on the adversary and the enemy”.

Nebuchadnezzar's marvellous blue and yellow bricks were an outstanding feature.

Although neither the technology of glazing nor the carving of the bricks was new, the combination was astonishing in its originality and artistic effect.

Neo-Babylonian decorative technology far surpassed earlier craftsmanship, and successive periods in Babylonia showed unglazed relief bricks, glazed flat bricks, and finally multi-coloured carved bricks.

These bricks were used to decorate most public monuments with carvings of animals, rosettes and palm trees in bright colours.

This sophisticated decoration was limited to a few structures that represented the power of the gods and the king. The most important of these was the complex of the Processional Way and the Ishtar Gate.

This road, coming from the north, was used during the New Year's festival procession by the gods along with the king and the court. At the end of this passage was the gate known as the Ishtar Gate, which was covered on all sides with enamelled bricks.

The walls of the Processional Way were lined with lions and other ornaments for about 180 metres in the lower sections, and were enhanced by a coloured stone floor leading into the city.

The impressive Ishtar Gate, composed of a gateway in the outer wall and the main gate in the great inner wall of the city, with a 48-metre long passageway, was decorated with no less than 575 animal images.

These images of bulls and dragons, representing sacred animals, were placed in alternating rows to provide a fitting setting for the New Year's procession that made its way to the Esagila, the sanctuary of Marduk, called the 'House Whose Top is High', in the centre of the city.

While Koldewey was busy excavating, his work received an unexpected boost when Jacques de Morgan (1857-1924), a French archaeologist, discovered the great stele of Hammurabi at the Persian site of Susa, inscribed with the famous code of laws, which was brought to the Louvre.

The stele had been plundered by the Elamites, Babylon's arch-enemies, and taken to modern-day Iran, where it was found by de Morgan.

Andrae was Koldewey's first assistant in the 1899-1903 Babylonian campaigns, but was later asked to lead a major excavation at Ashur, in northern modern-day Iraq. His contribution to the Babylonian discoveries can be seen mainly in the areas of documentation and reconstruction.

Publications on Babylon are still our most important sources on the temples and palaces of Nebuchadnezzar's city.

Andrae organised and supervised perhaps the most complex and impressive architectural reconstruction in the history of archaeology: the reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate and the Babylonian Processional Way in Berlin.

To carry out the reconstruction, the hundreds of glazed brick fragments from Babylon were first desalinised and carefully removed from their original location in Babylon.

The bricks were then reassembled in Berlin to form the lions, dragons, bulls and floral elements that originally decorated the monument. These figures were completed with new bricks fired in a specially designed kiln to achieve the correct colour and finish.

The reconstructions include the façades of the throne rooms, the front of the Ishtar Gate and an important part of the Processional Way.

The characteristics of German excavations, including the thoroughness of plans, inventories of finds, photographs and drawings, had a profound influence on the British Gerturde Bell (1868-1926), who visited the sites and corresponded with Koldewey and Andrae.

After World War I, as Iraq's first director of Antiquities, Bell established formal requirements for foreign excavators, including personal requirements, particularly a photographer for the excavation, and the sharing of finds with the newly formed Iraqi state.

Probably because of her admiration for Koldewey, Bell allowed most of the vast quantity of Babylonian finds left in Iraq after World War I to be sent to Germany in exchange for donations of reconstructed models and carvings for the new Iraqi national collection.

Over 500 boxes of enamelled bricks from Babylon were sent to Berlin. One of Bell's most important and enduring legacies is the Iraq Museum, founded in 1923 and opened in 1926.

Andrae recounts how they carried out the reconstruction work in Berlin: They immediately provided me with ample means and spacious rooms to work in, and I employed Willy Struck, who had about thirty assistants, and in two years he completed the gigantic work: seventy-two animal carvings and large bands of rosettes and ornaments.

I also found three Berlin pottery workshops, each of which made different attempts, in their own way, to imitate as closely as possible the six colours that can be distinguished on Babylonian bricks.

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate and the Processional Way was unveiled at the Vorderasiatisches Museum in 1930. Robert Koldewey did not live to see the completion of the reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate, because he died in 1925. His remains rest in a Berlin cemetery.

Thanks to the work of Koldewey and Andrae, part of the legacy of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II was recovered.

In ancient times, kings presented themselves as builders, as seen in the words of Nebuchadnezzar in the Book of Daniel: “Is not this the great Babylon I have built as the royal residence, by my mighty power and for the glory of my majesty?” (Daniel 4:30)

Koldewey's legacy is still alive. Thanks to his excavations, over 5,000 Babylonian tablets were recovered, as well as an overview of the great ancient Babylon. The veracity of the Jewish exile to Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar II was also proven.

There is still much to be discovered in ancient Iraq. For example, the tombs of the Babylonian kings have yet to be found.

Let us pray that future excavations will help us to better understand the history of Babylon, and that this will also help us to have a better understanding of the biblical text.

Arturo Terrazas, professor of Old Testament and academic dean at the IBSTE Faculty of Theology in Castelldefels, Catalonia (Spain).

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Archaeological Perspectives - Lions, bulls and dragons: Robert Koldewey and the discovery of Nebuchadnezzar II’s Babylon

.jpg)