E.1027 – Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea review: Graceful docudrama rehomes this evicted Irish design visionary

Selected cinemas; Cert 12A

Jealousy and skulduggery in the world of art and letters always has a slightly delicious taint to it. Feuds between writers and bandmates occupies a whole sub-genre in the biography category. Renaissance chronicler Giorgio Vasari delighted in telling his readers about the mutual disdain shared by Da Vinci and Michelangelo.

Why is this? Well, probably because it assures us that even those of lofty vision and creative brilliance can be just as petty and covetous as the rest of us. More so, perhaps.

How Franco-Swiss architectural giant Le Corbusier appropriated the credit for a house he didn’t build is the example portrayed in this docu-drama study of Irish design legend Eileen Gray.

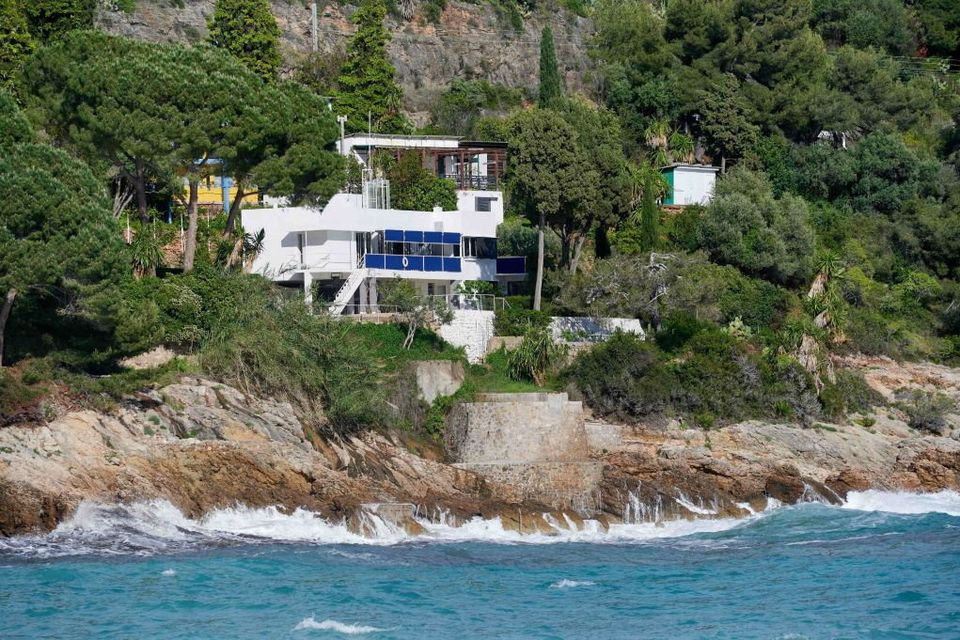

E.1027 was the name given to the modernist Cote d’Azur villa that Gray and architect lover Jean Badovici built for themselves in 1929. Seeking solitude in order to continue working, Gray vacated two summers after the building’s completion, leaving it to Badovici and taking up at a house 20 minutes further inland.

Badovici’s great friend Le Corbusier would often visit and stay at the seaside house after Gray’s departure. He would eventually paint murals on its bare walls, an act some have likened to territorial pissing over a building he felt drew from his influence.

Gray herself is said to have been appalled at this desecration of her intentionally plain walls. But it was in the aftermath of Badovici’s death that Le Corbusier’s obsession became clear. After failing to secure purchase of the house, he built a wooden shack in its shadow where he would die in 1965.

In those final years, it is said that he would never hurry to contradict any ascription of the house to his hand.

Villa E.1027, the house designed by Eileen Gray. Photo: Getty

It would be three years later that E.1027, now dilapidated and unloved, would be rediscovered in an architectural journal. The name Eileen Gray (who was still alive and living in obscurity) gradually became etched on the property as its chief visionary and developer.

Before long, the Enniscorthy-born trailblazer was at last getting the lavish retrospectives her genius merited. Her forgotten table and chair designs, meanwhile, would be mass produced for the homewares market. You might even be sitting on one at this very moment.

This film by Zurich co-directors Beatrice Minger and Christoph Schaub manages not to daub everything under the banner of revisionism and righting of misogynistic wrongs – and yet they are inescapable.

Initially a project about their fellow countryman Le Corbusier, the pair saw Gray and the erasing of her name from E.1027 were the real story.

Essayed with profound grace (and narrated in the first person) by Natalie Radmall-Quirke, Gray is seen as a pensive, focused creative who flees aristocratic privilege in rural Wexford for the melting pots of London and Paris.

Archive images of interwar decadence flash across a stage backdrop craftily adapted for various settings of the saga.

Relationships with both women and men (“men always wanted to compete or get married”) are never at the expense of a fierce drive to manifest in materials the lines and contours of her mind. By the time she meets the younger Badovici (Axel Moustache), her crosshairs are beginning to move from interior design to the chambers that will house it.

Le Corbusier (Charles Morillon) and his dominance in the field looms, but there is too much in Gray’s monologue (based on her writings) that alludes to single-mindedness.

A house, she reasoned, was shelter but also a body and a refuge, a place to be oneself at a time when homosexuals were being openly assaulted.

E.1027 would have no road access and sit just out of view; a clean, temporal abode to serve those inside rather than prying architectural sensibilities.

“People in a room become resonating bodies,” she says in one passage. “I wanted to create a space for the woman who needs a room of her own.”

It’s safe to say design is a realm rarely associated with this storied little island of ours. A luminary in that field – and a female one, at that – such as Gray should be spotlit at any occasion, not least for the attempts to erase her from history.

She’d approve of a tribute such as this, what with its stark but elliptical manoeuvres, its grace of form and composition, and the way in which it seems at once modern but somehow lived in.

Four stars

Have you tried Focail and Conundrum?

Daily word puzzles designed to test your vocabulary and lateral thinking skills.