Baltimore artist Bruce Willen is framed by a sign he created about long-buried Sumwalt Run.

You can’t spell “Baltimore” without “more” — as in more asphalt, more factories, more rowhouses, more parking garages, more office buildings, more of everything. But Bruce Willen’s new public art project invites observers to imagine Maryland’s most populous city with less.

The longtime Baltimorean has created a walking tour through a pair of neighborhoods just north of downtown along the former path of a streambed. There are 10 way-finding markers — soon to be 12 — along with wavy, light-blue ribbons of color slathered across the pavement.

The tour follows the story of rapidly changing demographics, rising and falling economic fortunes, and evolving attitudes toward nature. But mostly, the narrative revolves around water.

“Most people who live in the neighborhood,” Willen said as he gave a tour of the project on a foggy January morning, “they had no idea, unless they’re, like, a super history nerd, that the stream existed and still exists.”

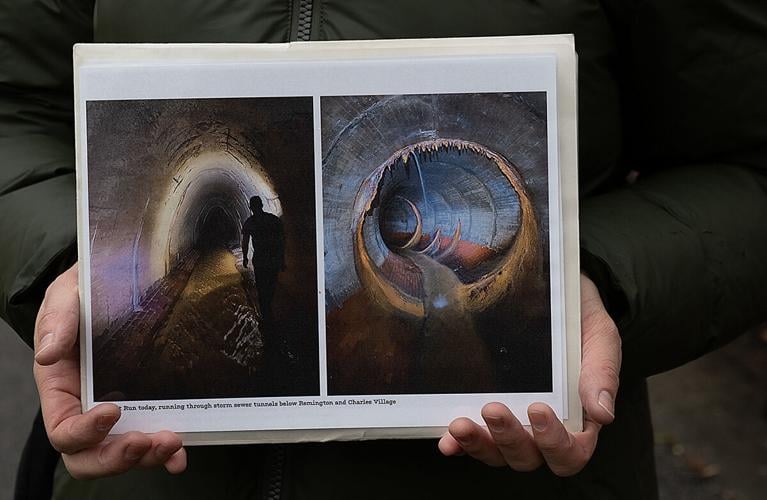

Baltimore artist Bruce Willen holds photographs he made inside the underground tunnel where Sumwalt Run now flows.

People may have forgotten. But the water hasn’t.

Sumwalt Run once meandered among tree roots and rocks at the bottom of a deep ravine. Mature beech and oak trees shaded the water. The stream zigzagged along the falling terrain for about 3 miles before spilling into the Jones Falls just north of North Avenue.

More than 100 years ago, as Baltimore’s inner core overflowed into the surrounding countryside, two neighborhoods — Remington and Charles Village — settled on top of the old waterway. Today, except for a few feet before its terminus, Sumwalt Run exists entirely underground, impounded within an aging storm sewer.

Willen’s project has brought the stream back to the surface. Not literally, of course. Multiple city blocks would have to be demolished for Sumwalt Run to experience daylight again. But here and there — bolting across a city street, hopping a curb, springing from the foot of a building — a stylized visual representation now traces the route of the buried stream.

Sumwalt Run is one of many streams in Baltimore that were paved over during the 1800s and early 1900s. It was a commonplace practice at that time in cities big and small, Willen explained. By entombing waterways underground, urban areas gained more (relatively) dry land for development. The practice also was seen as a boon to public health because many urban waterways had devolved into open sewers.

Willen named his project “Ghost Rivers.” The reason: “These waterways really are just ghostly presences,” he said. “They’re still there. You can hear them at certain points whispering up through the storm drains. And also, I think they do kind of haunt us.”

Artist Bruce Willen visits one of the stops on the Ghost Rivers trail that he created in the Remington neighborhood of Baltimore.

Willen’s project encompasses Sumwalt Run’s last downstream mile. He designed the tour to be self-guided. There is a sleek companion website (ghostrivers.com) with stop-by-stop directions, deeply researched historical accounts and archival photographs. But Willen also led small gatherings on tours shortly after the project’s initial completion last fall. More tours are set to take place this spring.

John Marra of Blue Water Baltimore, an environmental nonprofit engaged in monitoring and restoring the city’s waterways, co-hosts the tours with Willen.

“We’re trying to bring people knowledge of what’s under their feet constantly,” he said.

It’s more than historical curiosity, he added. Pipes like those that carry Sumwalt Run through the city offer no filtering of stormwater pollutants, such as sediment and nutrients. Those contaminants then flow into waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay, intensifying the estuary’s ecological headaches.

For Willen, art is a way of life. He owns a design outfit called Public Mechanics. Among the firm’s more notable works: the recent rebranding effort for the Baltimore Museum of Art, a series of chair sculptures outside the Anacostia Public Library in the District of Columbia and the graphics found throughout the Maryland Film Festival’s SNF Parkway Theatre.

The Ghost Rivers project began taking shape about a decade ago, as Willen tells it, when he stumbled across an old map of the Remington neighborhood, where he lives. On it, a stream was depicted where no stream now existed. That fact nestled into the deepest recesses of his mind, half-forgotten.

Fast forward to 2020, the year of the pandemic. He found himself spending a lot more time outdoors. During one of his walks among Remington’s brick-faced rowhouses and rehabilitated warehouses, the memory of that lost waterway came flooding back to him.

A painted line crosses a road in Baltimore’s Remington neighborhood as part of an art installation project by Bruce Willen that shows the path of long-buried Sumwalt Run.

“Walking around, I started encountering the stream at low-lying points. I’d hear the very faint sound of water coming up through the storm drains and remember, ‘Oh right, this is sort of where that stream on the little map was,’” Willen recalled. “That was the genesis.”

He drew further inspiration from another salient topic during that troubled year: the pitched conflicts in many cities over monuments to historical figures with ties to slavery.

“I was thinking about what a monument that is not actually to a person or event look like,” Willen said. “How can you have a remembrance of a landscape?”

In all, he cobbled together about $160,000 in grants to cover the project’s costs. Its backers include the Maryland State Arts Council, Gutierrez Memorial Fund, Maryland Heritage Areas Authority, Chesapeake Bay Trust, Baltimore City Department of Public Works and the utility contractor Spiniello.

His research was exhaustive and, at times, soggy. In addition to consulting historic photo archives and old plat maps, Willen ventured 30 feet beneath the city’s streets to find where Sumwalt Run now flows. Clad in wading boots, he splashed into a pitch-black storm sewer, trying not to slip on the algae-slickened floor.

The pipe was tall enough for him to stand in. Not far into his journey, Willen found himself shrouded in inky darkness. His flashlight beam revealed ever-changing construction materials: stone, mortar, brick, concrete. Stalactites loomed overhead. All the while, murky water gushed in its confined course at his feet.

In case this is not already obvious, the underground portion is not part of the tour. “It was a little sketchy,” he said. “I definitely don’t want to encourage anybody to try it.”

This tunnel carries Sumwalt Run under the streets of Baltimore.

Appropriately enough, the tour begins near the front steps of the Baltimore Museum of Art. The first stop is at Wyman Park Dell, a 16-acre park with a broad, grassy lawn and no shortage of shade. It’s notable in the context of Willen’s tour as the only place where the Sumwalt Run stream valley is still intact.

Much of the steep-sided park is sunken about 30 feet below the surrounding street grid. But the stream itself is nowhere to be seen. The park was designed by Olmsted Brothers Co., the landscape architecture firm behind Central Park. In their initial plans, the brothers sought to preserve the waterway. But, according to Willen’s research, they scrapped that idea after subsequent development on adjoining parcels all but obliterated the stream.

But now, things have come full circle. Community activists and conservation groups have been working citywide to capture and store rainfall at the surface to improve water quality. Some also hope to revive plans for the citywide network of green spaces envisioned by the Olmsteds.

Beyond Wyman Park Dell, there is virtually no evidence that a stream gully ever existed. The eye is greeted by block after block of rowhouses. With the blessing of the city’s public works department, Willen applied his wavy, light-blue artistic version of the Sumwalt Run streambed through this bustling urban landscape.

It’s made from the same material used for marking bike lanes, he said, making it “theoretically … a little bit more durable than paint.” The neighborhood association is formally responsible for the upkeep of the project.

The way-finding placards, fabricated from powder-coated steel and aluminum, are planted at various locations along the route. The signs tell of the stream and the environment. But they also unpack the history of the people who have resided here: the factory workers, the migrants from Appalachia, the waves of gentrification in recent years.

Willen hopes that his project enlightens people and perhaps even prods them to advocate for resurfacing Baltimore’s streams. This time, literally.

“We do talk a little bit about daylighting and some of the possibilities — not so much for this stream, but the Jones Falls,” he said. “It’s something that people have been talking about for a while. I would really love for this project to bring more conversation and have that conversation get taken more seriously.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

We aim to provide a forum for fair and open dialogue.

Please use language that is accurate and respectful.

Comments may not include:

* Insults, verbal attacks or degrading statements

* Explicit or vulgar language

* Information that violates a person's right to privacy

* Advertising or solicitations

* Misrepresentation of your identity or affiliation

* Incorrect, fraudulent or misleading content

* Spam or comments that do not pertain to the posted article

We reserve the right to edit or decline comments that do follow these guidelines.