Arts & Culture

Frederick-Born Designer Claire McCardell Single-Handedly Democratized Women’s Fashion

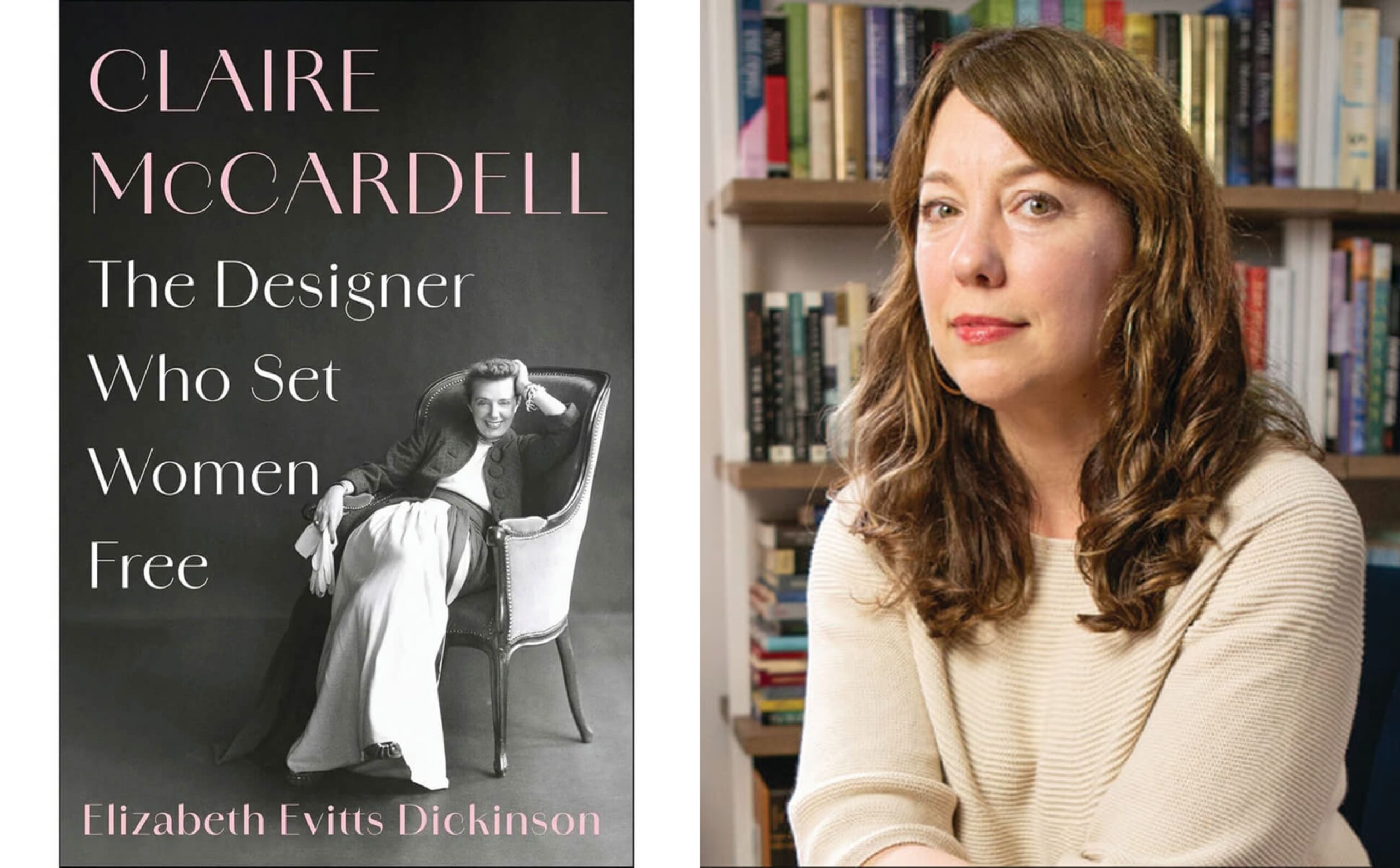

In her new biography, author Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson explores McCardell’s rise in the male-dominated midcentury New York fashion industry—ultimately giving us pockets, mix-and-match separates, and modern-day athleisure.

Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson has established herself as one of this city’s best writers. Crossing genres from narrative nonfiction to cultural criticism, short fiction, and memoir with signature intelligence and grace, her work has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Harper’s, The Washington Post Magazine, The Southern Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and Baltimore magazine, among other publications.

In 2018, Dickinson was a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellow, and in 2023, she became

the first literary artist in Maryland to win the Mary Sawyers Imboden Prize from the Baker Artist Awards.

In Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free, Dickinson puts her well-honed research skills and elegant prose into service to bring the extraordinary, if somewhat forgotten, Frederick-born designer to life.

This is more than a book about fashion, however. Through McCardell’s rise in the male-dominated New York fashion industry, Dickinson explores the evolving role of women in the workplace—the changes and challenges of the midcentury period—and her groundbreaking designs, which would ultimately become known as “the American Look.”

My grandmothers were Claire McCardell’s age. They worked so-called “pink-collar” jobs—bank secretary and cafeteria manager. They were creative, outdoorsy, and raised families, too. I felt like McCardell was designing for women like them.

When we hear the term “sportswear” today, we have on our modern filter, which translates to “athleisure”—like yoga pants. But the experience of your grandmothers describes the need for clothes that you could move in, clothes that you could work in. “Sportswear” became this catch-all term for essentially what became American fashion, like what Claire invented. There were these very practical considerations that became so interesting to me because they were as much about women’s autonomy as they were about women’s fashion.

How do you describe her design breakthrough?

One, she democratized design. She brought a form-meets-function thoughtfulness to design for women who didn’t have access to it. Previously, only women who were wealthy could afford really well-made clothes, primarily French haute couture. What Claire also saw was a need for a different kind of design that forefronted a woman’s true body. So, there wasn’t all this boning and corsets and structure. And she wanted to put it in American department stores and make it affordable and make it basically “ready to wear.” That didn’t exist.

Right. There is that Calvin Klein quote toward the end of the book, “She really invented sportswear, which is this country’s major contribution to fashion.”

The one place where Claire McCardell has never been forgotten is in the fashion-design field. Much of what we wear today came from her brilliant brain. The mix-and-match separate. She didn’t invent the idea of a wrap dress, but she pioneered the modern version of the wrap dress. She gave us ballet flats. Her inventions remain integral to our lives, even if her name is no longer associated with them.

One thing I love that you highlight is how her work takes place alongside the Modernist movement.

I see her very much in conversation with other Modernists. Painters like Georgia O’Keefe, architects like Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright. Industrial design is being invented. The Abstract Expressionism movement will take root later in female artists like Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Lee Krasner, the “Ninth Street” women. This was a magical moment in New York.

It’s funny, being a women’s fashion designer, how much she was influenced by growing up in rural Frederick and tree climbing, swimming, and skiing with her older brothers.

Claire McCardell was a rare designer who thought about the woman’s experience. She wasn’t worried about the male gaze or the societal gaze. Dior, who I write about, was very much about objectifying women, how they looked to the outside world, how they looked to men. She was concerned about a woman’s own experience and how she felt wearing the clothes, and what she did in those clothes.

Having three brothers absolutely informed her thinking. Not only about the design of clothes, but also the gendered nature of that design. She questioned why her brothers had pants with pockets, and she was trying to climb a tree in a dress and stockings.