Decades Ago, Painter Syd Solomon’s Phillippi Creek Home Became a Magical Gathering Spot for an Endless Stream of Famous Artists

Imagine growing up along the shores of Sarasota’s Phillippi Creek, back in the more bucolic 1950s and ’60s, in a house surrounded by lush vegetation—loquat, kumquat, tangerine, orange, grapefruit, mango and Surinam cherry trees providing fruit ripe for the picking. There, a child could run wild in a sort of organized jungle, catching fish and trapping blue crabs, playing atop ancient Indian middens (and dodging alligators) and visiting the neighbor next door who stored big glass jars of old arrowheads on the shelves of his kitchen.

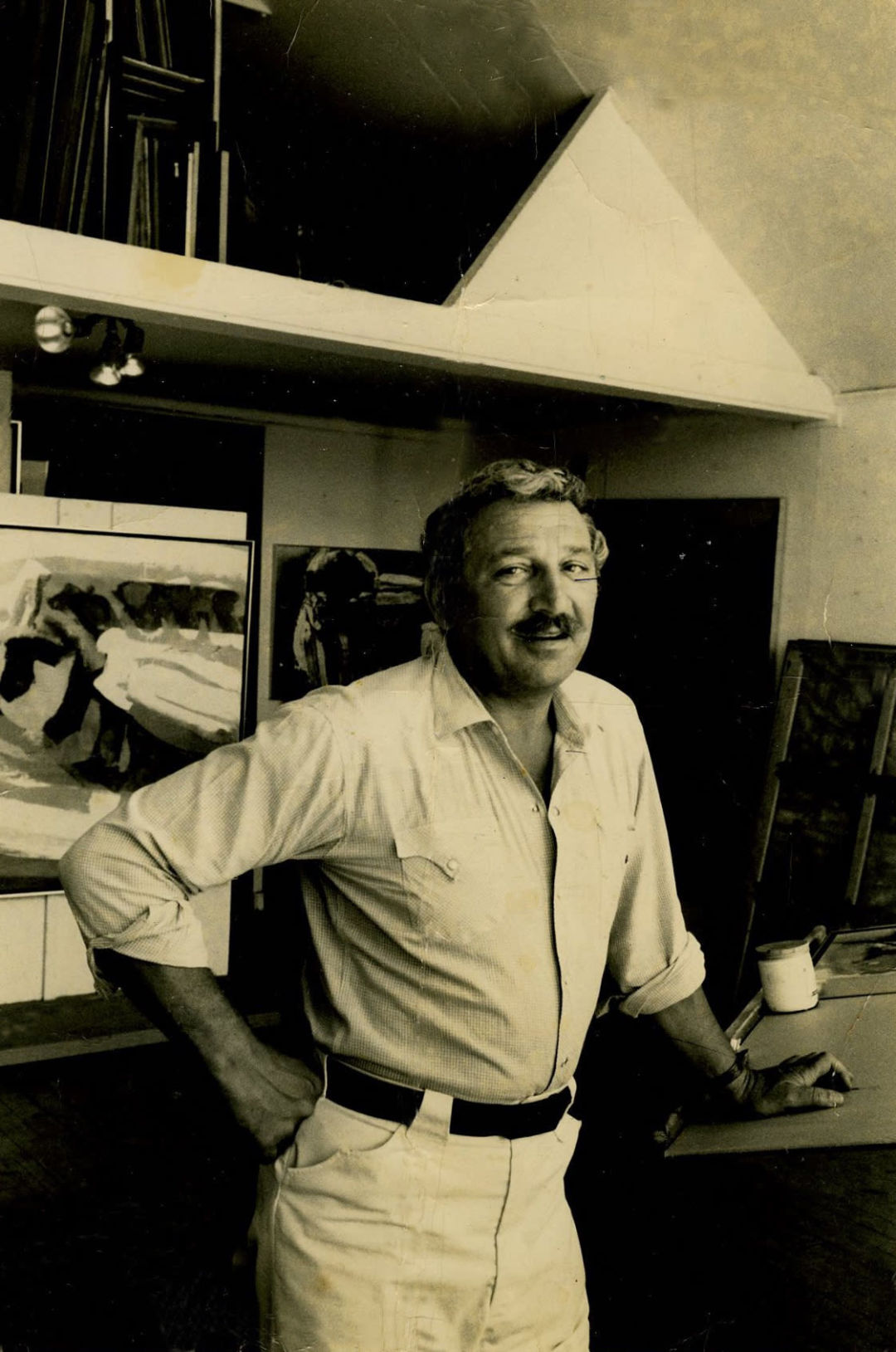

Image: Solomon Archives

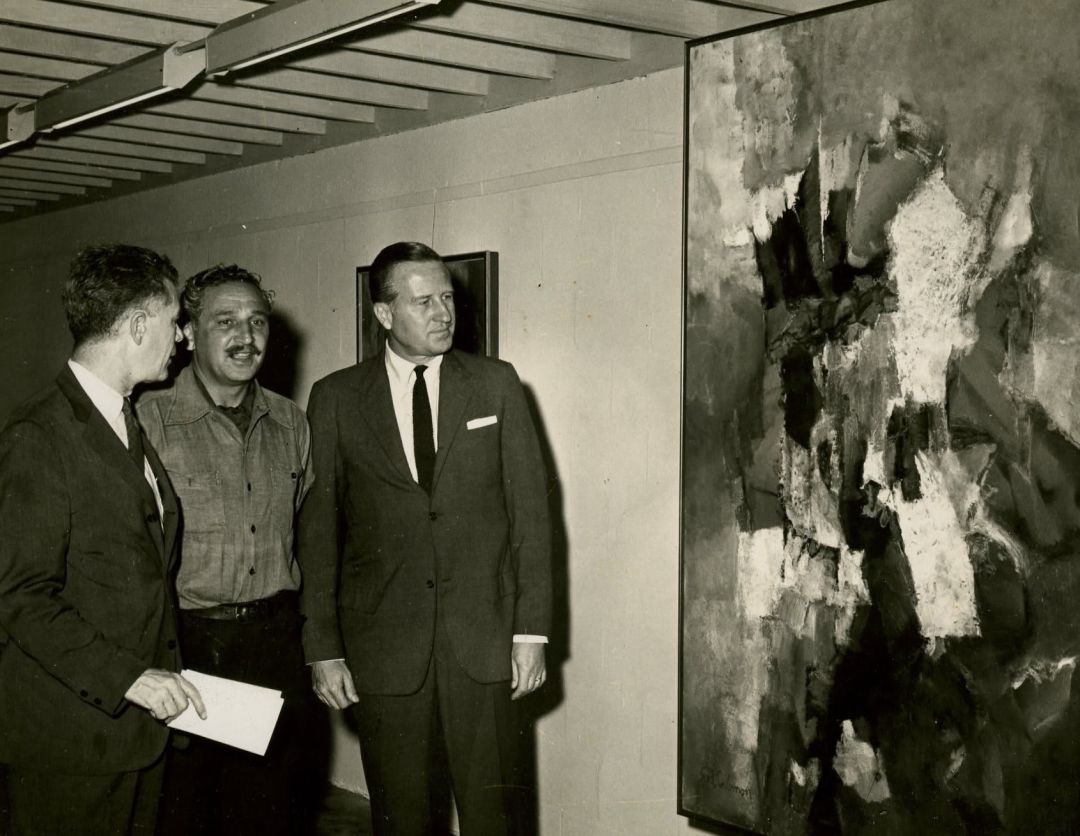

Image: Solomon Archives

Then imagine this as well: This house is also home to an artist’s studio with a northern light, as well as a Florida refuge for visiting artists, musicians and friends from all over the country who gather to get away from the cold, create new work, and enjoy convivial company.

This was the home, from 1950 to 1968, of famed Abstract Expressionist artist Syd Solomon, his wife, renowned hostess Annie, and their children, Michele and Mike. There, nature, painting, and sculpting, and an almost never-ending round of parties combined for what seems to have been an idyllic existence.

Image: Solomon Archives

That’s according to the memories of Mike Solomon, who spent most of his early years in that house on Portland Street. It was a home constructed at least 20 years prior to the Solomons’ acquisition of it, as a part of Sarasota’s historic Maine Colony—built by a group of Mainers who decided to make the neighborhood, bordered by Swift and Ashton roads, their winter getaway. Fittingly, the Solomon home was built by a man named Frank X. Jannelle, a Maine native who happened to be a friend of New England landscape and seascape painter Winslow Homer.

“I don’t think Jannelle was an artist,” says Mike Solomon, “but he was maybe a craftsman. He definitely built this house. One of the reasons it was so extraordinary was all the detail work—huge pecky cypress beams and a high level of craftsmanship that a New England builder would have had. It had these steep roofs—snow roofs [per New England weather expectations]—and huge oak trees with all the moss. It was a split-level house, with the first floor built on a high level, so underneath was a garage that led out to the river. When Jannelle built it, it had railroad tracks that led down to the river. There was just so much mystery as a child living there.” (By the way, the house still stands today.)

Image: Solomon Archives

Image: Solomon Archives

The Solomons, so well-known as leaders of the Sarasota artists’ and writers’ colony, first arrived here on Jan. 1, 1946—the same day the Ringling Museum opened officially to the public. Syd, a World War II vet who had suffered frostbite during the Battle of the Bulge, was looking for a warm weather escape, and the couple first found a home on 39th Street, relatively near the museum. They became fast friends with the museum’s new and forward-thinking director, Arthur Everett “Chick” Austin Jr., who had just left his position at Connecticut’s prestigious Wadsworth Atheneum to lead the Ringling.

With the birth of their first child, Michele, the Solomons moved to a home on Oleander Street for a while, but, says Mike, “Both places were tiny, and Syd needed a studio. As he turned towards painting and working larger, the idea of having a real studio and the romantic appeal of that house on Phillippi came together. They just loved it.”

Image: Solomon Archives

Image: Solomon Archives

Image: Solomon Archives

The one thing Syd did architecturally to the house, says Mike, was building an addition he called “the cage.” A screened-in area with a patio floor, the two-story cage was big and welcoming enough to become a focal point for dancing and entertaining when the Solomons’ friends came to visit and sometimes stayed for long stretches. One of those friends, Mike recalls, was an artist named Gabriel Kohn, who had been in the military with Syd. Needing a place to stay, he came to live with the Solomons for several months, staying in “the pad,” a little bedroom with a shower under the cage’s bar area.

Mike vividly remembers watching Kohn make maquettes for his sculptures in his work area at the house. “As far as I know, the closest Gabe came to having a kid around was me,” he says. “I got to watch him make art. I tried to imitate what he was doing, and he loved that.”

Another artist who was a frequent presence at the Phillippi house was fellow AbEx painter David Budd. Budd, who married circus equestrian artist Corcaita “Corky” Cristiani and briefly attended the Ringling School of Art, wanted to become an abstract artist, so he called Syd one day, and Annie picked up. “David said, ‘I’ve heard about Syd and I wondered if I could come over sometime,’” says Mike. “Annie said, ‘What are you doing now?’ He came over and that was it”—leading to a years-long friendship and productive artistic career.

Another outgrowth of that friendship was Budd’s suggesting the Solomons travel to the Hamptons in New York in the summer. “David and Corky invited my parents there in 1955, they met Jackson Pollock, and the rest is history,” is the way Mike puts it.

Image: Solomon Archives

Image: Solomon Archives

Image: Solomon Archives

As the Solomons came to divide their time between Sarasota and the Hamptons, their roster of artist friends continued to expand. “Our house had probably three parties a week, an endless stream of all these people,” Mike marvels. “As I got a little older, I began to comprehend it. [Folksinger] Eric von Schmidt [something of a mentor to Bob Dylan in his early days] would come and sit on the couch with the river behind him during a party and play for half an hour or so. It was extraordinary.”

Whether in the Hamptons or here, the Solomons also began to spend more time with artist Conrad Marca-Relli and his wife, Anita; with Philip Guston and his wife, painter-poet Musa McKim; with James Brooks and his painter wife, Charlotte Park. In such an environment, it’s not surprising that by the time he was in his teens, Mike knew he wanted to be an artist.

Image: Solomon Archives

Image: Solomon Archives

Of course, for a kid, transitioning between two different homes and facing an interrupted school year had its down sides. “What was weird for me was breaking in and out of peer groups when I was an adolescent,” says Mike. And at the age of about 12, he adds, “I was about to get into trouble with some of the more redneck inhabitants” of the neighborhood.

So, while it was “heartbreaking” to him when his parents decided to sell the Phillippi house in 1968 and move to Siesta Key, “I’m so grateful, really,” he says. “Over the years, I’ve learned that Syd was always obsessed with Midnight Pass, from the 1940s on. Back then, you went there by boat mostly. Syd had some buddies there, and I think he realized, ‘There’s all this property available in the place I love more than any on the planet.’ He wanted to build an artists’ community, saving the place from developers. He was afraid it would become condominium-ized.” (A prediction that certainly came true on much of Siesta Key.)

Image: Solomon Archives

Image: Solomon Archives

So, not only the Phillippi house but their property in East Hampton was sold so Syd could build his dreamed-about Siesta house. That home and studio, on Blind Pass Road, was the site of many more memorable artistic and entertaining experiences, prior to its eventual loss due to beach erosion escalating in the 1980s. (Solomon and a neighbor filled in Midnight Pass in 1984 to save their homes, but Solomon’s home was eventually condemned and razed in the early 2000s.)

The Siesta Key house, built by architect Gene Leedy and a prize-winning design, is the Sarasota home people most often associate with Syd Solomon and his work. But the Phillippi house has a special place in Mike’s heart, too—so much so that he recently presented a slide show and talk about it at the neighborhood’s historic Phillippi Crest Community Clubhouse, a community center more than 100 years old.

Mike, who's now in his 60s, is also writing a memoir (working title: Our Salon by the Sea) that tells the decades-long tale of two art worlds—the Hamptons and Sarasota—where the Solomons made their home. “It’s not an art theory book,” he says. “It’s a lot of me talking about these people’s work and why I think it’s important—what they tried to achieve, and they achieved a lot. I first tried to do this when I was about 50, but I've finally found the voice for it. It’s not my story, but I do put myself into the story, in my interactions with these people, in that world.” He’s hoping to finish the book by the end of next year.